10/1/2021

Original is here.

We made it into October!! Spooky, spooky!

Corrections

Like in real newspapers (Links to an external site.), we are going to start including Corrections in each edition! We want to make sure that our reporters adhere to the highest standards:

The JVM will insert an implicit call to the to-be-instantiated class’ default constructor (i.e., the one with no parameters) if the the to-be-constructed (sub)class does not do so explicitly. We’ll make this clear with an example:

class Parent {

Parent() {

System.out.println("I am in the Parent constructor.");

}

Parent(int parameter) {

System.out.println("This version of the constructor is not called.");

}

}

class Child extends Parent {

Child() {

/*

* No explicit call to super -- one is automatically

* injected to the parent constructor with no parameters.

*/

System.out.println("I am in the Child constructor.");

}

}

public class DefaultConstructor {

public static void main(String args[]) {

Child c = new Child();

}

}

When this program is executed, it will print

I am in the Parent constructor.

I am in the Child constructor.

The main function is instantiating an object of the type Child. We can visually inspect that there is no explicit call the super() from within the Child class’ constructor. Therefore, the JVM will insert an implicit call to super() which actually invokes Parent().

However, if we make the following change:

class Parent {

Parent() {

System.out.println("I am in the Parent constructor.");

}

Parent(int parameter) {

System.out.println("This version of the constructor is not called.");

}

}

class Child extends Parent {

Child() {

/*

* No explicit call to super -- one is automatically

* injected to the parent constructor with no parameters.

*/

super(1);

System.out.println("I am in the Child constructor.");

}

}

public class DefaultConstructor {

public static void main(String args[]) {

Child c = new Child();

}

}

Something different happens. We see that there is a call to Child’s superclass’ constructor (the one that takes a single int-typed parameter). That means that the JVM will not insert an implicit call to super() and we will get the following output:

This version of the constructor is not called. I am in the Child constructor.

The C++ standard sanctions a main function without a return statement. The standard says: “if control reaches the end of main without encountering a return statement, the effect is that of executing return 0;.”

A Different Way to OOP

So far we have talked about OOP in the context of Java. Java, and languages like it, are called Class-based OOP languages. In a Class-based OOP, classes and objects exist in different worlds. Classes are used to define/declare

- the attributes and methods of an encapsulation, and

- the relationships between them.

From these classes, objects are instantiated that contain those attributes and methods and respect the defined/declared hierarchy. We can see this in the example given above: The classes Parent and Child define (no) attributes and (no) methods and define the relationship between them. In main(), a Child is instantiated and stored in the variable c. c is an object of type Child that contains all the data associated with a Child and a Parent and can perform all the actions of a Child and a Parent.

Nothing about Class-based OOP should be different than what you’ve learned in the past as you’ve worked with C++. There are several problems with Class-based OOP.

- The supported attributes and method of each class must be determined before the application is developed (once the code is compiled and the system is running, an object cannot add, remove or modify its own methods or attributes);

- The inheritance hierarchy between classes must be determined before the application is developed (once the code is compiled, changing the relationship between classes will require that the application be recompiled!).

In other words, Class-based OOP does not allow the structure of the Classes (nor their relationships) to easily evolve with the implementation of a system.

There is another way, though. It’s called Prototypal OOP. The most commonly known languages that use Prototypal OOP are JavaScript and Ruby! In Prototypal (which is a very hard word to spell!) OOP there is no distinction between Class and object – everything is an object! In a Prototypal OOP there is a base object that has no methods or data attributes and every object is able to modify itself (its attributes and methods). To build a new object, the programmer simply copies from an existing object, the new object’s so-called prototype, and customizes the copied object appropriately.

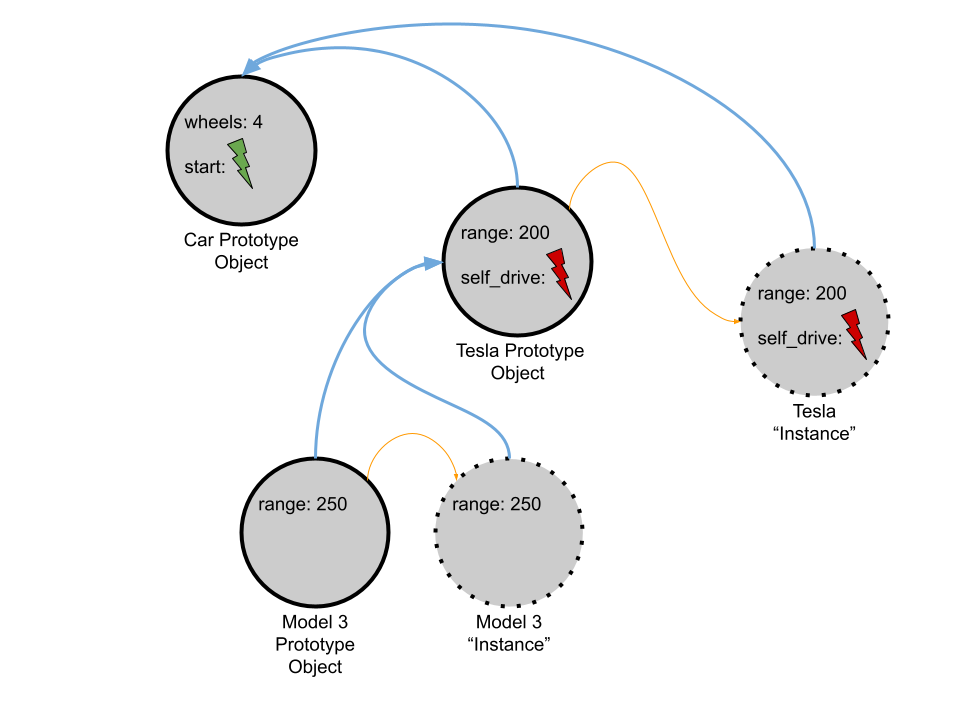

For example, assume that there is an object called Car that has one attribute (the number of wheels) and one method (start). That object can serve as the prototype car. To “instantiate” a new Car, the programmer simply copies the existing prototypical car object Car and gives it a name, say, c. The programmer can change the value of c’s number of wheels and invoke its method, start. Let’s say that the same programmer wants to create something akin to a subclass of Car. The programmer would create a new, completely fresh object (one that has no methods or attributes), name it, say, Tesla, and link the new prototype Tesla object to the existing prototype car Car object through the prototype Tesla object’s prototype link (the sequence of links that connects prototype objects to one another is called a prototype chain). If a Tesla has attributes (range, etc) or methods (self_drive) that the prototype car does not, then the programmer would install those methods on the prototype Tesla Tesla. Finally, the programmer would “declare” that the Tesla object is a prototype Tesla.

The blue arrows in the diagram above are prototype links. The orange lines indicate where a copy is made.

How does inheritance work in such a model? Well, it’s actually pretty straightforward: When a method is invoked or an attribute is read/assigned, the runtime will search the prototype chain for the first prototypical object that has such a method or attribute. Mic drop. In the diagram above, let’s follow how this would play out when the programmer calls start() on the Model 3 Instance. The Model 3 Instance does not contain a method named start. So, up we go! The Tesla Prototype Object does not contain that me either. All the way up! The Car Prototype Object, does, however, so that method is executed!

What would it look like to override a function? Again, relatively straightforward. If a Tesla performs different behavior than a normal Car when it starts, the programmer creating the Tesla Prototype Object would just add a method to that object with the name start. Then, when the prototype chain is traversed by the runtime looking for the method, it will stop at the start method defined in the Tesla Prototype Object instead of continuing on to the start method in the Car Prototype Object. (The same is true of attributes!)

There is (at least) one really powerful feature of this model. Keep in mind that the prototype objects are real things that can be manipulated at runtime (unlike classes which do not really exist after compilation) and prototype objects are linked together to achieve a type of inheritance. With reference to the diagram above, say the programmer changes the definition of the start method on the Car Prototype Object. With only that change, any object whose prototype chain includes the Car Prototype Object will immediately have that new functionality (where it is not otherwise overridden, obviously) – all without stopping the system!! How cool is that?

How scary is that? Can you imagine working on a system where certain methods you “inherit” change at runtime?

OOP or Interfaces?

Newer languages (e.g., Go, Rust, (new versions of) Java) are experimenting with new features that support one of the “killer apps” of OOP: The ability to define a function that takes a parameter of type A but that works just the same as long as it is called with an argument whose type is a subtype of A. The function doesn’t have care whether it is called with an argument whose type is A or some subtype of A because the language’s OOP semantics guarantee that anything the programmer can do with an object of type A, the programmer can do with and object of subtype of A.

Unfortunately, using OOP to accomplish such a feat may be like killing a fly with a bazooka (or a laptop, like Alex killed that wasp today).

Instead, modern languages are using a slimmer mechanism known as an interface or a trait. An interface just defines a list of methods that an implementer of that interface must support. Let’s see some real Go code that does this – it’ll clear things up:

type Readable interface {

Read()

}

This snippet defines an interface with one function (Read) that takes no parameters and returns no value. That interface is named Readable. Simple.

type Book struct {

title string

}

This snippet defines a data structure called a Book – such structs are the closest that Go has to classes.

func (book Book) Read() {

fmt.Printf("Reading the book %v\n", book.title)

}

This snippet simply says that if variable b is of type Book then the programmer can call b.Read(). Now, for the payoff:

func WhatAreYouReading(r Readable) {

r.Read()

}

This function only accepts arguments that implement (i.e., meet the criteria specified in the definition of) the Readable interface. In other words, with this definition, the code in the body of the function can safely assume that it can can call Read on r. And, for the encore:

book := Book{title: "Infinite Jest"}

WhatAreYouReading(book)

This code works exactly like you’d expect. book is a valid argument to WhatAreYouReading because it implements the Read method which, implicitly, means that it implements the Readable interface. But, what’s really cool is that the programmer never had to say explicitly that Book implements the Readable interface! The compiler checks automatically. This gives the programmer the ability to generate a list of only the methods absolutely necessary for its parameters to implement to achieve the necessary ends – and nothing unnecessary. Further, it decouples the person implementing a function from the person using the function – those two parties do not have to coordinate requirements beforehand. Finally, this functionality means that a structure can implement as few or as many interfaces as its designer wants.

Dip Our Toe Into the Pool of Pointers

We only had a few minutes to start pointers, but we did make some headway. There will be more on this in the next lecture!

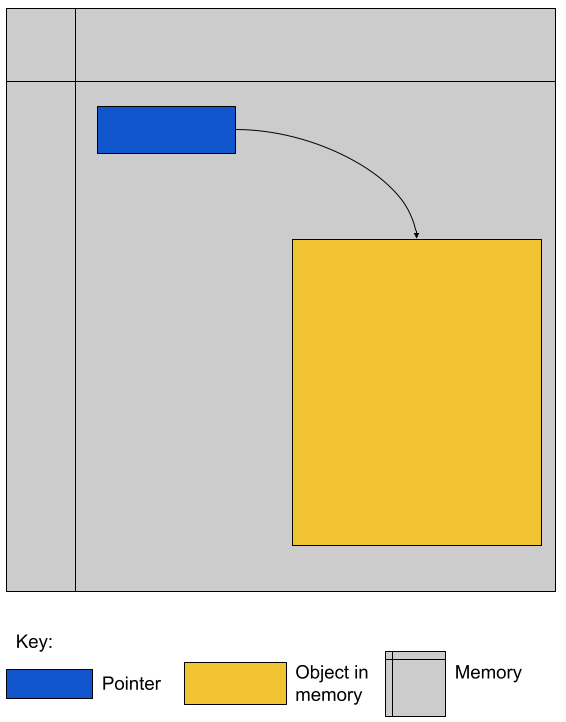

It is important to remember that pointers are like any other type – they have a range of valid values and a set of valid operations that you can perform on those values. What are the range of valid values for a pointer? All valid memory addresses. And what are the valid operations? Addition, subtraction, dereference and assignment.

In the diagram, the gray area is the memory of the computer. The blue box is a pointer. It points to the gold area of memory. It is important to remember that pointers and their targets both exist in memory! In fact, in true Inception (Links to an external site.)style, a pointer can pointer to a pointer!

At the same time that pointers are types, they also have types. The type of a pointer includes the type of the target object. In other words, if the memory in the gold box held an object of type T, the the green box’s type would be “pointer to type T.” If the programmer dereferences the blue pointer, they will get access to the object in memory in the gold.

In an ideal scenario, it would always be the case that the type of the pointer and the type of the object at the target of the pointer are the same. However, that’s not always the case. Come to the next lecture to see what can go wrong when that simple fact fails to hold!