10/27/2021

The Tail That Wags the Dog

There are no loops in functional programming languages. We’ve learned that, instead, functional programming languages are characterised by the fact that they use recursion for control flow. As we discussed earlier in the class (much earlier, in fact), when running code on a von Neumann machine, iterative algorithms typically perform faster than recursive algorithms because of the way that the former leverages the properties of the hardware (e.g., spatial and temporal locality of code ). In addition, recursive algorithms typically use much more memory than iterative algorithms.

Why? To answer that question, we will need to recall what we learned about stack frames. For every function invocation, an activation record (aka stack frame) is allocated on the run-time stack (aka call stack). The function’s parameters, local variables, and return value are all stored in its activation record. The activation record for a function invocation remains on the stack until it has completed execution. In other words, if a function f invokes a function g, then function f’s activation record remains on the stack until (at least) g has completed execution.

Consider some algorithm A. Let’s assume that an iterative implementation of A requires n executions of a loop and l local integer variables. If that implementation is contained in a function, an invocation of that function would consume approximately l*sizeof(integer variable) + activation record overhead space on the runtime stack. Let’s further assume that a function implementing the recursive version of A also uses l local integer variables and also requires n executions of itself. Each invocation of the implementing function, then, needs l*sizeof(integer variable) + activation record overhead space on the runtime stack. Multiply that by n, the number of recursive calls, and you can see that, at it’s peak, executing the recursive version of algorithm A requires n * (l * sizeof(integer variable) + activation record overhead) space on the run-time stack. In other words, the recursive version requires n times more memory! That escalated quickly .

That’s all very abstract. Let’s look at the implications with a real-world example, which we will write in Haskell syntax:

myLen [] = 0

myLen (x:xs) = 1 + (myLen xs)

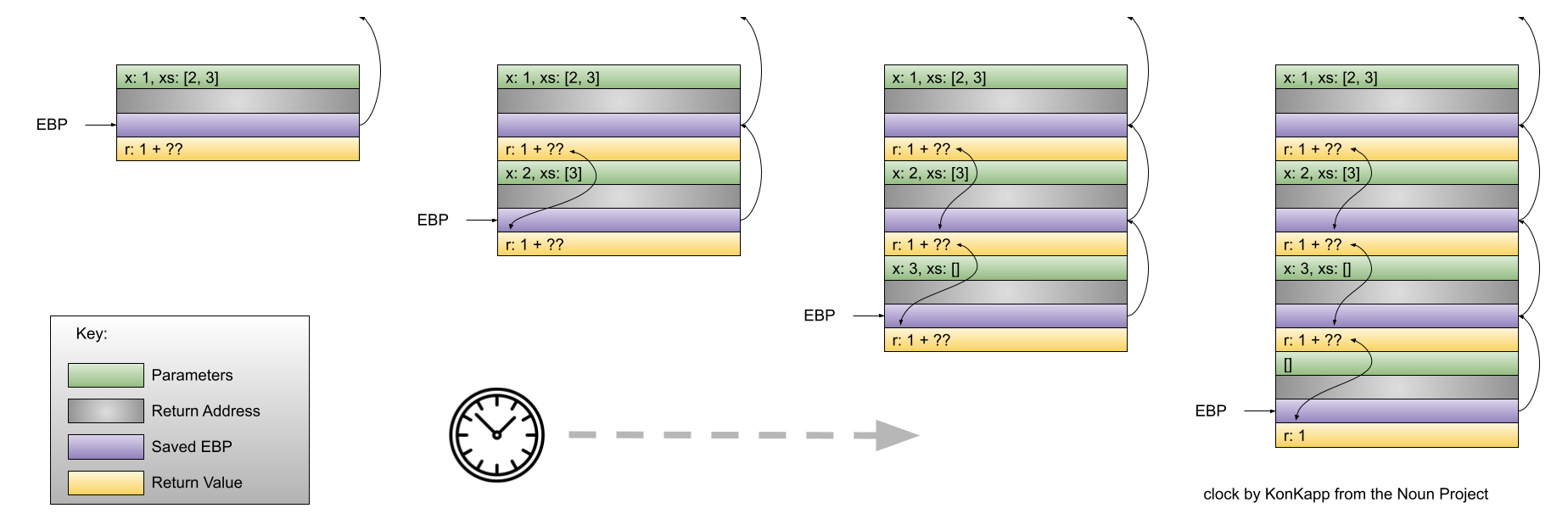

myLen is a function that recursively calculates the length of a list. Let’s see what the stack would look like when we call myLen [1,2,3]:

When the recursive implementation of myLen reaches the base case, there are four activation records on the run-time stack.

Allocating space on the stack takes time. Therefore, the more activation records placed on the stack, the more time the program will take to execute. But, if we are willing to live with a slower program, then there’s nothing else to worry about.

Right?

Wrong. Modern hardware is fast. Modern computers have lots of memory. Unfortunately, they don’t have an infinite amount of memory. A program only has a finite amount of stack space. Given a long enough list, myLen could cause so many activation records to be placed on the stack that the amount of stack space is exhausted and the program crashes. In other words, it’s not just that a recursive algorithm might execute slower, a recursive algorithm might fail to calculate the correct result entirely!

Tail Recursion - Hope

The activation records of functions that recursively call themselves remain on the stack because, presumably, they need the result of the recursive invocation to complete their work. For example, in our myLen function, an invocation of myLen cannot completely calculate the length of the list given as a parameter until the recursive call completes.

What if there was some way to rewrite a recursive function in a way that it did not need to wait on a future recursive invocation to completely calculate its result? If that could happen, then the stack frame of the current invocation of the function could be replaced by the stack frame of the recursive invocation. Why? Because the information contained in the current invocation of the function has no bearing on its overall result – the only information needed to completely calculate the result of the function is the result of the future recursive invocation! The implementation of a recursive function that matches this specification is known as a tail-recursive function. The book says “A function is tail recursive if its recursive call is the last operation in the function.”

With a tail-recursive function, we get the expressiveness of a recursive definition of the algorithm along with the efficiency of an iterative solution! Ron Popeil, that’s a deal!

Rewriting

The rub is that we need to figure out a way to rewrite those non-tail recursive functions into tail-recursive versions. I am not aware of any general purpose algorithms for such a conversion. However, there is one technique that is widely applicable: accumulators. It is sometimes possible to add a parameter to a non-tail recursive function and use that parameter to define a tail-recursive version. Seeing an accumulator in action is the easiest way to define the technique. Let’s rewrite myLen in a tail-recursive manner using an accumulator:

myLen list = myLenImpl 0 list

myLenImpl acc [] = acc

myLenImpl acc (x:xs) = myLenImpl (1 + acc) xs

First, notice how we are turning myLen into a function that simply invokes a worker function whose job is to do the actual calculation! The first parameter to myLenImpl is used to hold a running tally of the length of the list so far. The first invocation of myLenImpl from the implementation of myLen, then, passes 0 as the argument to the accumulator because the running tally of the length so far is, well, 0. The implementation of myLenImpl adds 1 to that accumulator variable for every list item that is stripped from the front of the list. The result is that the result of an invocation of myLenImpl does not rely on the completion of a recursive execution. Therefore, myLenImpl qualifies as a tail-recursive function! Woah.

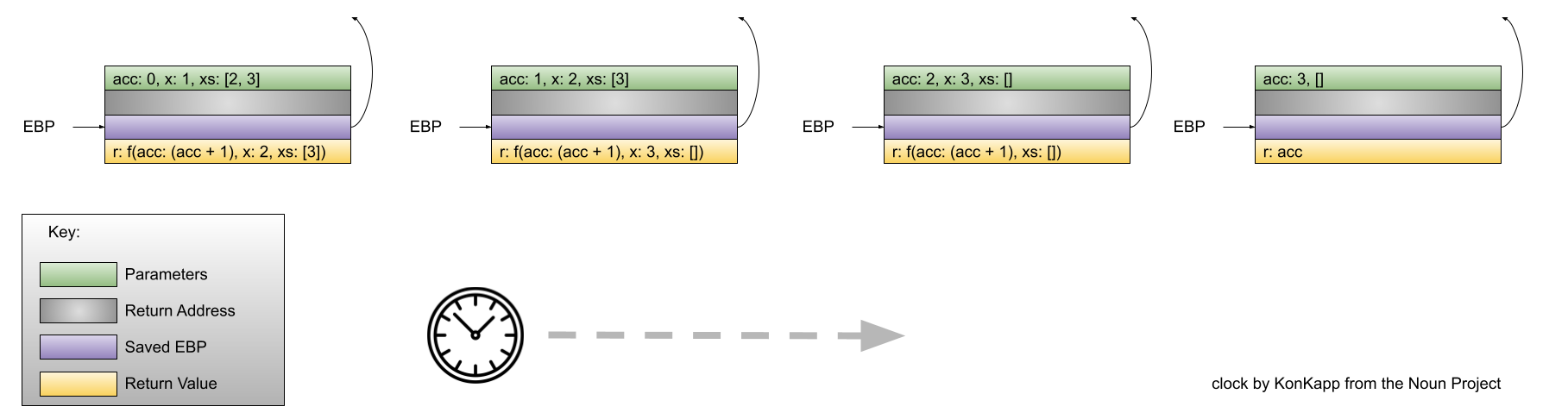

Let’s look at the difference in the contents of the run-time stack when we use the tail-recursive version of myLen to calculate the length of the list [1,2,3]:

A constant amount of stack space is being used – amazing!