10/4/2021

Original is here One day closer to Candy Corn!

Corrections

When we were discussing the nature of the type of pointers, we specified that the range of valid values for a pointer are all memory addresses. In some languages this may be true. However, some other languages specify that the range of valid values for a pointer are all memory addresses and a special null value that explicitly specifies a pointer does not point to a target.

We also discussed the operations that you can perform on a pointer-type variable. What we omitted was a discussion of an operation that will fetch the address of a variable in memory. For languages that use pointers to support indirect addressing (see below), such an operation is required. In C/C++, this operation is performed using the address of (&) operator.

Pointers

We continued the discussion of pointers that we started on Friday! On Friday we discussed that pointers are just like any other type – they have valid values and defined operations that the programmer can perform on those values.

The Pros of Pointers

Though a very famous and influential computer scientist (Links to an external site.) once called his invention of null references a “billion dollar mistake” (he low balled it, I think!), the presence and power of pointers in a language is important for at least two reasons:

- Without pointers, the programmer could not utilize the power of indirection.

- Pointers give the programmer the power to address and manage heap-dynamic memory.

Indirection gives the programmer the power to link between different objects in memory – something that makes writing certain data structures (like trees, graphs, linked lists, etc) easier. Management of heap-dynamic memory gives the programmer the ability to allocate, manipulate and deallocate memory at runtime. Without this power, the programmer would have to know before execution the amount of memory their program will require.

The Cons of Pointers

Their use as a means of indirection and managing heap-dynamic memory are powerful, but misusing either can cause serious problems.

Possible Problems when Using Pointers for Indirection

As we said in the last lecture, as long as a pointer targets memory that contains the expected type of object, everything is a-okay. Problems arise, however, when the target of the pointer is an area in memory that does not contain an object of the expected type (including garbage) and/or the pointer targets an area of memory that is inaccessible to the program.

The former problem can arise when code in a program writes to areas of memory beyond their control (this behavior is usually an error, but is very common). It can also arise because of a use after free. As the name implies, a use-after-free error occurs when a program uses memory after it has been freed. There are two common scenarios that give rise to a use after free:

- Scenario 1:

- One part of a program (part A) frees an area of memory that held a variable of type T that it no longer needs

- Another part of the program (part B) has a pointer to that very memory

- A third part of the program (part C) overwrites that “freed” area of memory with a variable of type S

- Part B accesses the memory assuming that it still holds a variable of Type T

- Scenario 2:

- One part of a program (part A) frees an area of memory that held a variable of type T that it no longer needs

- Part A never nullifies the pointer it used to point to that area of memory though the pointer is now invalid because the program has released the space

- A second part of the program (part C) overwrites that “freed” area of memory with a variable of type S

- Part A incorrectly accesses the memory using the invalid pointer assuming that it still holds a variable of Type T

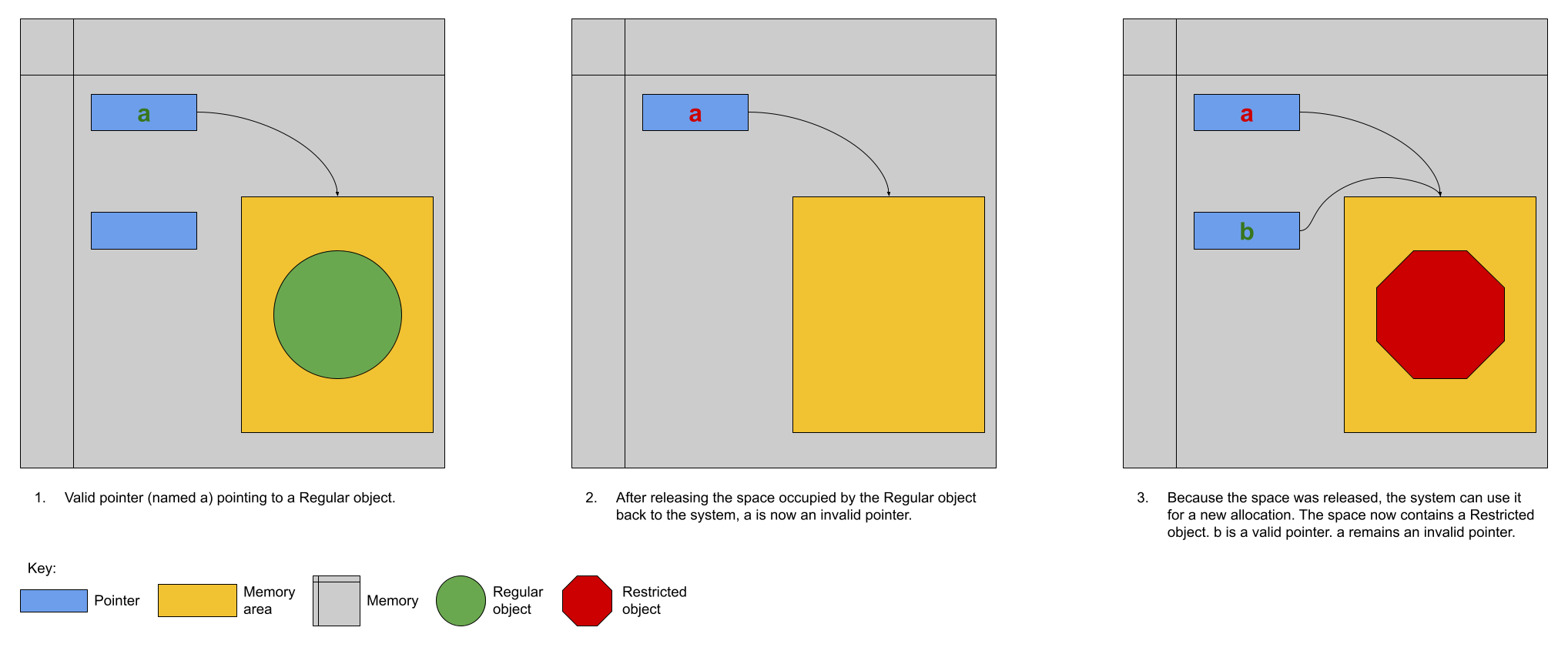

Scenario 2 is depicted visually in the following scenario and intimates why use-after-free errors are considered security vulnerabilities:

In the example shown visually above, the program’s use of the invalid pointer means that the user of the invalid pointer can now access an object that is at a higher privilege level (Restricted vs Regular) than the programmer intended. When the programmer calls a function through the invalid pointer they expect that a method on the Regular object will be called. Unfortunately, a method on the Restricted object will be called instead. Trouble!

The latter problem occurs when a pointer targets memory beyond the program’s control. This most often occurs when the program sets a variable’s address to 0 (NULL, null, nil) to indicate that it is invalid but later uses that pointer without checking its validity. For compiled languages this often results in the dreaded segmentation fault and for interpreted languages it often results in other anomalous behavior (like Java’s Null Pointer Exception (NPE)). Neither are good!

Possible Solutions

Wouldn’t it be nice if we had a way to make sure that the pointer being dereferenced is valid so we fall victim to some of the aforementioned problems? What would be the requirements of such a solution?

- Pointers to areas of memory that have been deallocated cannot be dereferenced.

- The type of the object at the target of a pointer always matches the programmer’s expectation.

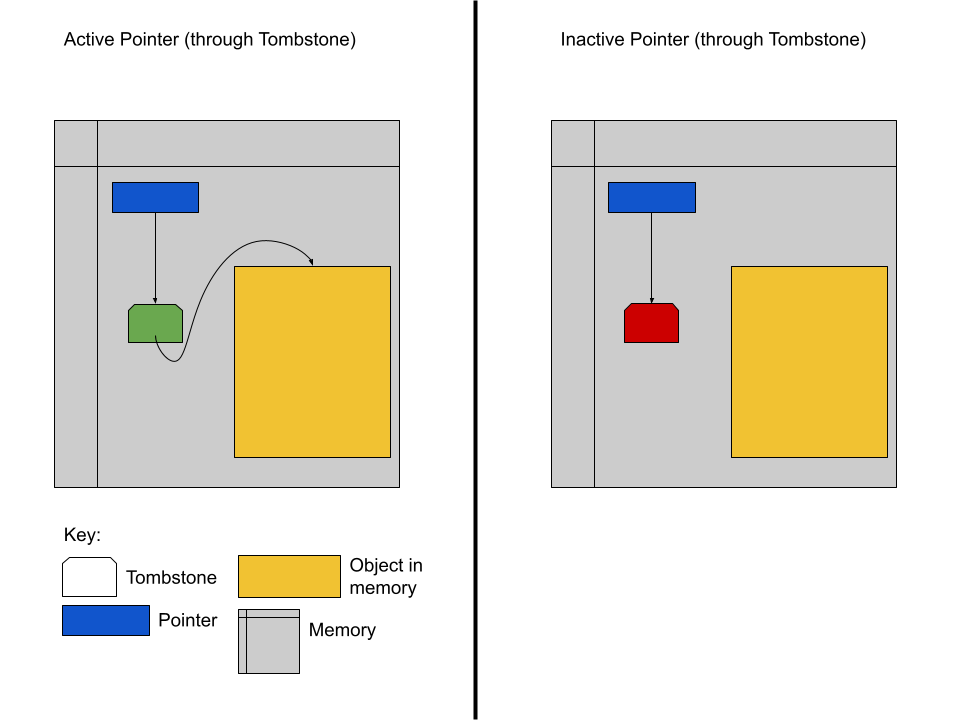

Your author describes two potential ways of doing this. First, are tombstones. Tombstones are essentially an intermediary between a pointer and its target. When the programming language implements pointers and uses tombstones for protection, a new tombstone is allocated for each pointer the programmer generates. The programmer’s pointer targets the tombstone and the tombstone targets the pointer’s actual target. The tombstone also contains an extra bit of information: whether it is valid. When the programmer first instantiates a pointer to some target a the compiler/interpreter

- generates a tombstone whose target is a

- sets the valid bit of the tombstone to valid

- points the programmer’s pointer to the tombstone.

When the programmer dereferences their pointer, the compiler/runtime will check to make sure that the target tombstone’s valid flag is set to valid before doing the actual dereference of the ultimate target. When the programmer “destroys” the pointer (by releasing the memory at its target or by some other means), the compiler/runtime will set the target tombstone’s valid flag to invalid. As a result, if the programmer later attempts to dereference the pointer after it was destroyed, the compiler/runtime will see that the tombstone’s valid flag is invalid and generate an appropriate error.

This process is depicted visually in the following diagram.

Tombstones.png

This seems like a great solution! Unfortunately, there are downsides. In order for the tombstone to provide protection for the entirety of the program’s execution, once a tombstone has been allocated it cannot be reclaimed. It must remain in place forever because it is always possible that the programmer can incorrectly reuse an invalid pointer. As soon as the tombstone is deallocated, the protection that it provides is gone. The other problem is that the use of tombstones adds an additional layer of indirection to dereference a pointer and every indirection causes memory accesses. Though memory access times are small, they are not zero – the cost of these additional memory accesses add up.

What about a solution that does not require an additional level of indirection? There is a so-called lock-and-key technique. This protection method requires that the pointer hold an additional piece of information beyond the address of the target: the key. The memory at the target of the pointer is also required to hold a key. When the system allocates memory it sets the keys of the pointer and the target to be the same value. When the programmer dereferences a pointer, the two keys are compared and the operation is only allowed to continue if the keys are the same. The process is depicted visually below.

With this technique, there is no additional memory access – that’s good! However, there are still downsides. First, there is a speed cost. For every dereference there must be a check of the equality of the keys. Depending on the length of the key that can take a significant amount of time. Second, there is a space cost. Every pointer and block of allocated memory now must have enough space to store the key. For systems where memory allocations are done in big chunks, the relative size overhead of storing, say, and 8byte key is not significant. However, if the system allocates many small areas of memory, the relative size overhead is tremendous. Moreover, the more heavily the system relies on pointers the more space will be used to store keys rather than meaningful data.

Well, let’s just make the keys smaller? Great idea. There’s only one problem: The smaller the keys the fewer unique key values. Fewer unique key values mean that it is more likely an invalid pointer randomly points to a chunk of memory with a matching key. In this scenario, the protection afforded by the scheme is vitiated. (I just wanted to type that word – I’m not even sure I am using it correctly!)