10/6/2021

Original is here.

I love Reese’s Pieces.

Corrections

None to speak of!!

Pointers for Dynamic Memory Management

We finished up our discussion of pointers in today’s class. In the previous class, we talked about how pointers have two important roles in programming languages:

- indirection – referring to other objects

- dynamic memory management – “handles” for areas of memory that are dynamically allocated and deallocated by the system.

On Monday we focused on the role of pointers in indirection and how to solve some of the problems that can arise from using pointers in that capacity. In today’s class, we focused on the role of pointers in dynamic memory management.

As tools for dynamic memory management, the programmer can use pointers to target blocks (N.B.: I am using blocks as a generic term for memory and am not using it in the sense of a block [a.k.a. page] as defined in the context of operating systems) of dynamic memory that are allocated and deallocated by the operating system for use by an application. The programmer can use these pointers to manipulate what is stored in those blocks and, ultimately, release them back to the operating system when they are no longer needed.

Memory in the system is a finite resource. If a program repeatedly asks for memory from the system without releasing previous allocations back to the system, there will come a time when the memory is exhausted. In order to be able to release existing allocations back to the operating system for reuse by other applications, the programmer must not lose track of those existing allocations. When there is a memory allocation from the operating system to the application that can no longer be reached by a pointer in the application, that memory allocation is leaked. Because the application no longer has a pointer to it, there is no way for the application to release it back to the system. Leaked memory belongs to the leaking application until it terminates.

For some programs this is fine. Some applications run for a short, defined period of time. However, there are other programs (especially servers) that are written specifically to operate for extended periods of time. If such applications leak memory, they run the risk of exhausting the system’s memory resources and failing (Links to an external site.).

Preventing Memory Leaks

System behavior will be constrained when those systems are written in languages that do not support using pointers for dynamic memory management. However, what we learned (above) is that it is not always easy to use pointers for dynamic memory management correctly. What are some of the tools that programming languages provide to help the programmer manage pointers in their role as managers of dynamic memory.

Reference Counting

In a reference-counted memory management system, each allocated block of memory given to the application by the system contains a reference count. That reference count, well, counts the number of references to the object. In other words, for every pointer to an operating-system allocated block of memory, the reference count on that block increases. Every time that a pointer’s target is changed, the programming language updates the reference counts of the old target (decrement) and the new target (increment), if there is a new target (the pointer could be changed to null, in which case there is no new target). When a block’s reference count reaches zero, the language knows that the block is no longer needed, and automatically returns it to the system! Pretty cool.

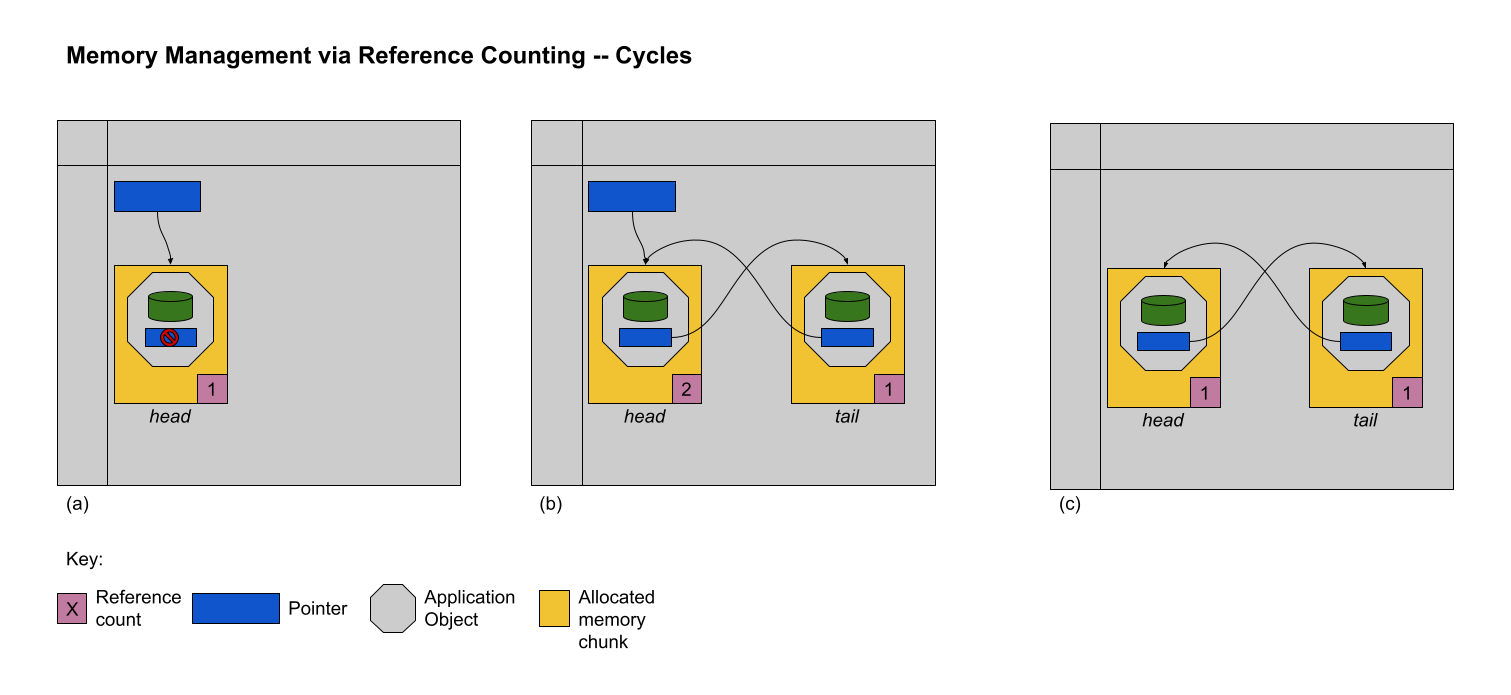

The scenario depicted visually shows the reference counting process. At time (a), the programmer allocates a block of memory dynamically from the operating system and puts an application object in that block. Assume that the application object is a node in a linked list. The first node is the head of the list. Because the programmer has a pointer that targets that allocation, the block’s reference count at time (a) is 1. At time (b), the programmer allocates a second block of memory dynamically from the system and puts a second application object in that block – another node in the linked list (the tail of the list). Because the head of the list is referencing the tail of the list, the reference count of the tail is 1. At time (c) the programmer deletes their pointer (or reassigns it to a different target) to the head of the linked list. The programming language decrements the reference count of the block of memory holding the head node and deallocates it because the reference count has dropped to 0. Transitively, the pointer from the head application object to the tail application object is deleted and the programming language decrements the reference count of its target, the block of memory holding the tail application object (time (d)). The reference count of the block of memory holding the tail application object is now 0 and so the programming language automatically deallocates the associated storage (time (e)). Voila – an automatic way to handle dynamic memory management.

There’s only one problem. What if the programmer wants to implement a circularly linked list?

Because the tail node points to the head node, and the head node points to the tail node, even after the programmer’s pointer to the head node is deleted or retargeted, the reference counts of the two nodes will never drop to 0. In other words, even with reference-counted automatic memory management, there could still be a memory leak! Although there are algorithms to break these cycles, it’s important to remember that reference counting is not a panacea. Python is a language that manages memory using reference counting.

Garbage Collection

Garbage collection (GC) is another method of automatically managing dynamically allocated memory. In a GC’d system, when a programmer allocates memory to store an object and no space is available, the programming language will stop the execution of the program (a so-called GC pause) to calculate which previously allocated memory blocks are no longer in use and can be returned to the system. Having freed up space as a result of cleaning up unused garbage, the allocation requested by the programmer can be satisfied and the execution of the program can continue.

The most efficient way to engineer a GC’d system is if the programming language allocates memory to the programmer in fixed-size cells. In this scenario, every allocation request from the programmer is satisfied by a block of memory from one of several banks of fixed-size blocks that are stacked back-to-back. For example, a programming language may manage three different banks – one that holds reserves of X-sized blocks, one that holds reserves of Y-sized blocks and one that holds reserves of Z-sized blocks. When the programmer asks for memory to hold an object that is of size a, the programming language will deliver a block that is just big enough to that object. Because the size of the requested allocation may not be exactly the same size as one of the available fixed-size blocks, space may be wasted.

The fixed sizing of blocks in a GC’d system makes it easy/fast to walk through every block of memory. We will see shortly that the GC algorithm requires such an operation every time that it stops the program to do a cleanup. Without a consistent size, traversing the memory blocks would require that each block hold a tag indicating its size – a waste of space and the cause of an additional memory read – so that the algorithm could dynamically calculate the starting address of the next block.

When the programmer requests an allocation that cannot be satisfied, the programming language stops the execution of the program and does a garbage collection. The classic GC algorithm is called mark and sweep and has three steps:

Every block of memory is marked as free using a free bit attached to the block. Of course, this is only true of some of the blocks, but the GC is optimistic! All pointers active at the time the program is paused are traced to their targets. The free bits of those blocks are reset. The blocks that are marked free and released.

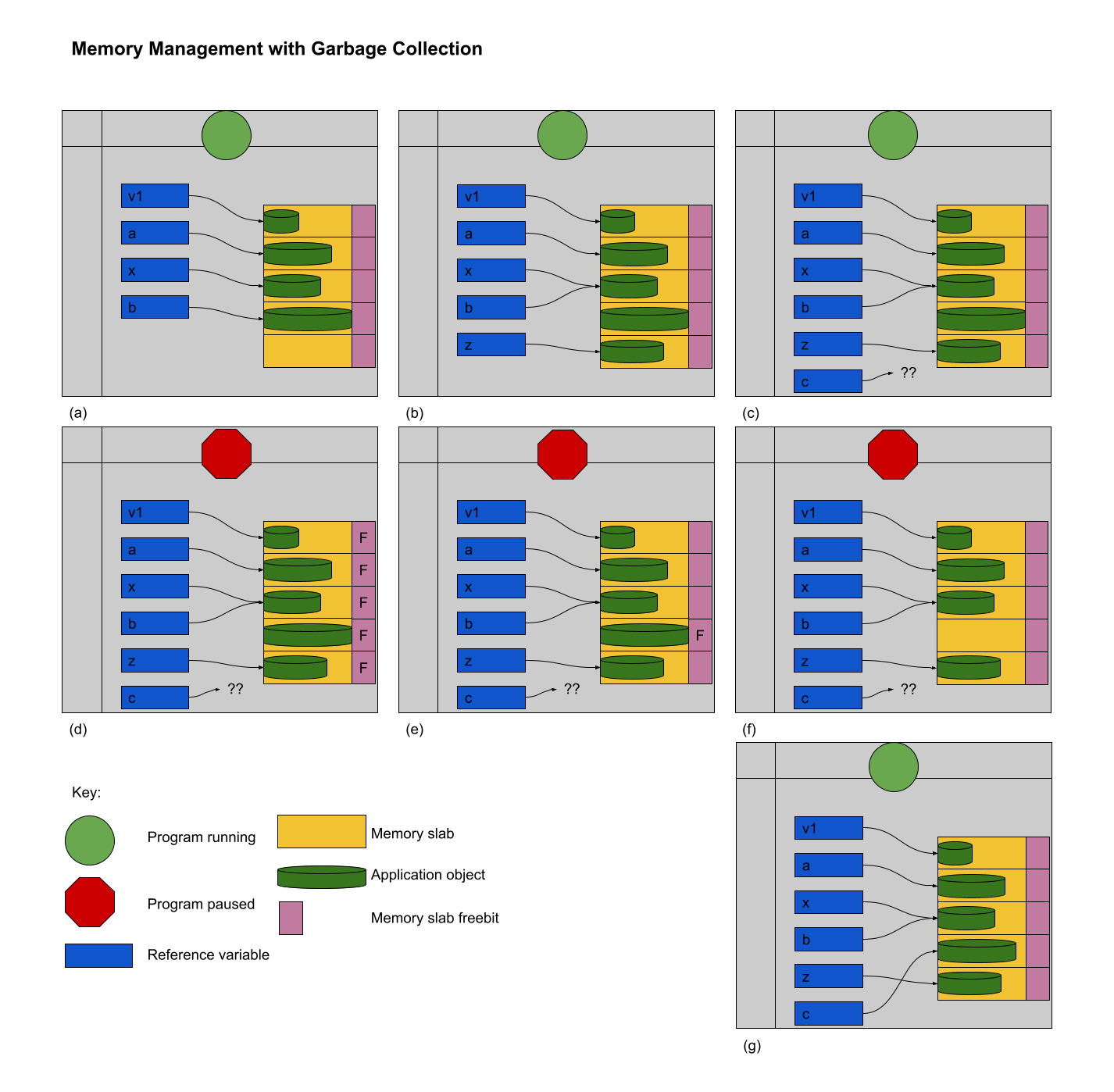

The process is shown visually below:

At times (a), (b) and (c), the programmer is allocating and manipulating references to dynamically allocated memory. At time (c), the allocation request for variable z cannot be satisfied because there are no available blocks. A GC pause starts at time (d) and the mark-and-sweep algorithm commences by setting the free bit of every block. At time (e) the pointers are traced and the appropriate free bits are cleared. At time (f) the memory is released from the unused block and its free bit, too, is reset. At time (g) the allocation for variable z can be satisfied, the GC pause completes and the programming language restarts execution of the program.

This process seems great, just like reference counting seemed great. However, there is a significant problem: The programmer cannot predict when GC pauses will occur and the programmer cannot predict how long those pauses will take. A GC pause is completely initiated by the programming language and (usually) completely beyond the control of the programmer. Such random pauses of program execution could be extremely harmful to a system that is controlling a system that needs to keep up with interactions from the outside world. For instance, it would be totally unacceptable for an autopilot system to take an extremely long GC pause as it calculates the heading needed to land a plane. There are myriad other systems where pauses are inappropriate.

The mark-and-sweep algorithm described above is extremely naive and GC algorithms are the subject of intense research. Languages like go and Java manage memory with a GC and their algorithms are incredibly sophisticated. If you want to know more, please let me know!