11/1/2021

Your Total Is …

In today’s class, we started with writing a simple function to sum the numbers in a list and ended up with the definition of a fundamental operation of functional programming: the fold. Let’s start by writing the simple, recursive definition of a sum function in Haskell:

simpleSum [] = 0

simpleSum (first:rest) = first + (simpleSum rest)

When invoked with the list [1,2,3,4], the result is 10:

*Summit> simpleSum [1,2,3,4]

10

Exactly what we expected. Let’s think about our job security: The boss tells us that they want a function does “products” all the elements in the list. Okay, that’s easy:

simpleProduct [] = 1

simpleProduct (first:rest) = first * (simpleProduct rest)

When invoked with the list [1,2,3,4], the result is 24:

*Summit> simpleProduct [1,2,3,4]

24

Notice that there are only minor differences between the two functions: the value returned in the base case (0 or 1) and the operation being performed on head and the result of the recursive invocation.

I hear some of your shouting at me already: This isn’t tail recursive; you told us that tail recursive functions are important. Fine! Let’s rewrite the two functions so that they are tail recursive. We will do so using an accumulator and a helper function:

trSimpleSum list = trSimpleSumImpl 0 list

trSimpleSumImpl runningTotal [] = runningTotal

trSimpleSumImpl runningTotal (x:xs) = trSimpleSumImpl (runningTotal + x) xs

When invoked with the list [1,2,3,4], the result is 10:

*Summit> trSimpleSum [1,2,3,4]

10

And, we’ll do the same for the function that calculates the product of all the elements in the list:

trSimpleProduct list = trSimpleProductImpl 1 list

trSimpleProductImpl runningTotal [] = runningTotal

trSimpleProductImpl runningTotal (x:xs) = trSimpleProductImpl (runningTotal * x) xs

When invoked with the list [1,2,3,4], the result is 24:

*Summit> trSimpleProduct [1,2,3,4]

24

One of These Things is Just Like The Other

Notice the similarities between trSimpleSumImpl and trSimpleProductImpl. Besides the names, the only difference is really the operation that is performed on the runningTotal and the head element of the list. Because we’re using a functional programming language, what if we wanted to let the user specify that operation in terms of a function parameter? Such a function would need have to accept two arguments (the up-to-date running total and the head element) and return a new running total. For summing, we might write a sumOperation function:

sumOperation runningTotal headElement = runningTotal + headElement

Next, instead of defining trSimpleSumImpl and trSimpleProductImpl with fixed definitions of their operation, let’s define a trSimpleOpImpl that could use sumOperation:

trSimpleOpImpl runningTotal operation [] = runningTotal

trSimpleOpImpl runningTotal operation (x:xs) = trSimpleOpImpl (operation runningTotal x) operation xs

Fancy! Now, let’s use trSimpleOpImpl and sumOperation to recreate trSimpleSum from above:

trSimpleSum list = trSimpleOpImpl 0 sumOperation list

Let’s check to make sure that we get the same results: When invoked with the list [1,2,3,4], the result is 10:

*Summit> trSimpleSum [1,2,3,4]

10

To confirm our understanding of what’s going on here, let’s visualize the invocations of sumOperation necessary to complete the calculation of trSimpleSum:

sumOperation 0 1

sumOperation 1 2

sumOperation 3 3

sumOperation 6 4

Let’s do a similar thing for trSimpleProduct:

productOperation runningTotal headElement = runningTotal * headElement

trSimpleProduct list = trSimpleOpImpl 0 productOperation list

Let’s check to make sure that we get the same results: When invoked with the list [1,2,3,4], the result is 24:

*Summit> trSimpleProduct [1,2,3,4]

24

Think About the Types:

We’ve stumbled on a pretty useful pattern! Let’s look at its components:

- A “driver” function (called trSimpleOpImpl) that takes three parameters: an initial value (of a particular type, T), an operation function (see below) and a list of inputs, each of which is of type T.

- An operation function that takes two parameters – a running total, of some type R; an element to “accumulate” on to the running total of type T – and returns a new running total of type R.

- A list of inputs, each of which is of type T.

Here are the types of those functions in Haskell:

operation function: R -> T -> R

list of inputs: [T]

driver function: T -> (R -> T -> R) -> R

Let’s play around and see what we can write using this pattern. How about a concatenation of a list of strings in to a single string?

concatenateOperation concatenatedString newString = concatenatedString ++ newString

concatenateStrings list = trSimpleOpImpl "" concatenateOperation list

(the ++ just concatenates two strings together). When we run this on [“Hello”, “,”, “World”] the result is “Hello, World”:

*Summit> concatenateStrings ["Hello", ",", "World"]

"Hello,World"

So far our Ts and Rs have been the same – integers and strings. But, the signatures indicate that they could be different types! Let’s take advantage of that! Let’s use trSimplOpImpl to write a function that returns True if every element in the list is equal to the number 1 and False otherwise. Let’s call the operation function continuesToBeAllOnes and define it like this:

continuesToBeAllOnes equalToOneSoFar maybeOne = equalToOneSoFar && (maybeOne == 1)

This function will return True if the list (to this point) has contained all ones (equalToOneSoFar) and the current element (maybeOne) is equal to one. In this case, the R is a boolean and the T is an integer. Let’s implement a function named isListAllOnes using continuesToBeAllOnes and trSimplOpImpl:

isListAllOnes list = trSimpleOpImpl True continuesToBeAllOnes list

Does it work? When invoked with the list [1,1,1,1], the result is True:

*Summit> isListAllOnes [1,1,1,1]

True

When invoked with the list [1,2,1,1], the result is False:

*Summit> isListAllOnes [1,2,1,1]

False

Naming those “operation” functions every time is getting annoying, don’t you think? I bet that we could be lazier!! Let’s rewrite isListAllOnes without specifically defining the continuesToBeAllOnes function:

isListAllOnes list = trSimpleOpImpl True (\equalToOneSoFar maybeOne -> equalToOneSoFar && (maybeOne == 1)) list

Now we are really getting functional!

I am greedy. I want to write a function that returns True if any element of the list is a one:

isAnyElementOne list = trSimpleOpImpl False (\anyOneSoFar maybeOne -> anyOneSoFar || (maybeOne == 1)) list

This is just way too much fun!

Fold the Laundry

This type of function is so much fun that it is included in the standard implementation of Haskell! It’s called fold! And, in true Haskell fashion, there are two different versions to maximize flexibility and confusion: the fold-left and fold-right operation. The signatures for the functions are the same in both cases:

fold[l,r] :: operation function -> initial value -> list -> result

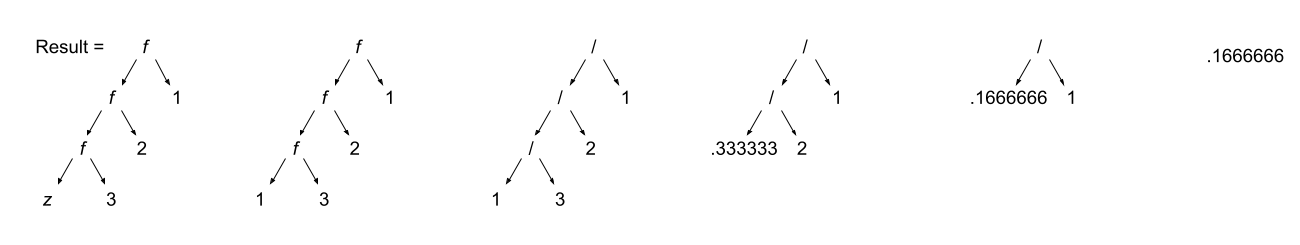

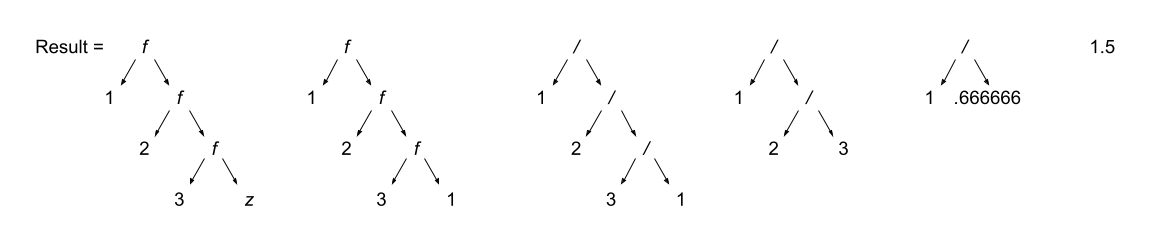

In all fairness, these two versions are necessary. Why? Because certain operation functions are not associative! It doesn’t matter the order in which you add or multiply a series of numbers – the result of (5 * (4 * (3 *2))) is the same as (((5 * 4) * 3) * 2). The problem is, that’s not the case of an operation like division!

A fold-left operation (foldl) works by starting the operation (essentially) from the first element of the list and the fold-right operation (foldr) works by starting the operation (essentially) from the last element of the list. Furthermore, the choice of foldl vs foldr affects the order of the parameters to the operation function: in a foldl, the running value (which is known as the accumulator in mainstream documentation for fold functions) is the left parameter; in a foldr, the accumulator is the right parameter.

This will make more sense visually, I swear:

*Summit> foldl (\x y -> x /y ) 1 [3,2,1]

0.16666666666666666

*Summit> foldr (\x y -> x / y ) 1 [3,2,1]

1.5

Let’s use our newfound fold power, to recreate our work from above:

isAnyElementOne list = foldl (\anyOneSoFar maybeOne -> anyOneSoFar || (maybeOne == 1)) False list

isListAllOnes list = foldl (\equalToOneSoFar maybeOne -> equalToOneSoFar && (maybeOne == 1)) True list

concatenateStrings list = foldl (\concatenatedString newString -> concatenatedString ++ newString) "" list