11/10/2021

In today’s class we learned about a workhorse rule in logic programming: append/3. append/3 can be used to implement many other different rules, including a rule that will generate all the permutations of a list!

Pin the Tail on the List

The goal (pun intended) of append is to determine whether two lists, X and Y, are the same as a third list, Z, when appended together. We could use the append query like this:

?- append([1,2,3], [a,b,c], [1,2,3,a,b,c]).

true.

or

?- append([1,2,3], [a,b], [1,2,3,a,b,c]).

false.

What we will find is that append/3 has a hidden superpower besides its ability to simply answer yes/no queries like the ones above.

The definition of append/3 will follow the pattern of other recursively defined rules that we have seen so far. Let’s start with the base case. The result of appending an empty list with some list Y, is just list Y. Let’s write that down:

append([], Y, Y).

And now for the recursive case: appending list X to list Y yields some list Z where Z is the first element of the list X following by the result of appending the tail of X with Y. The natural language version of the definition is complicated but I think that the Prolog definition makes it more clear:

append([H|T], Y, [H|AppendedList]) :- append(T, Y, AppendedList).

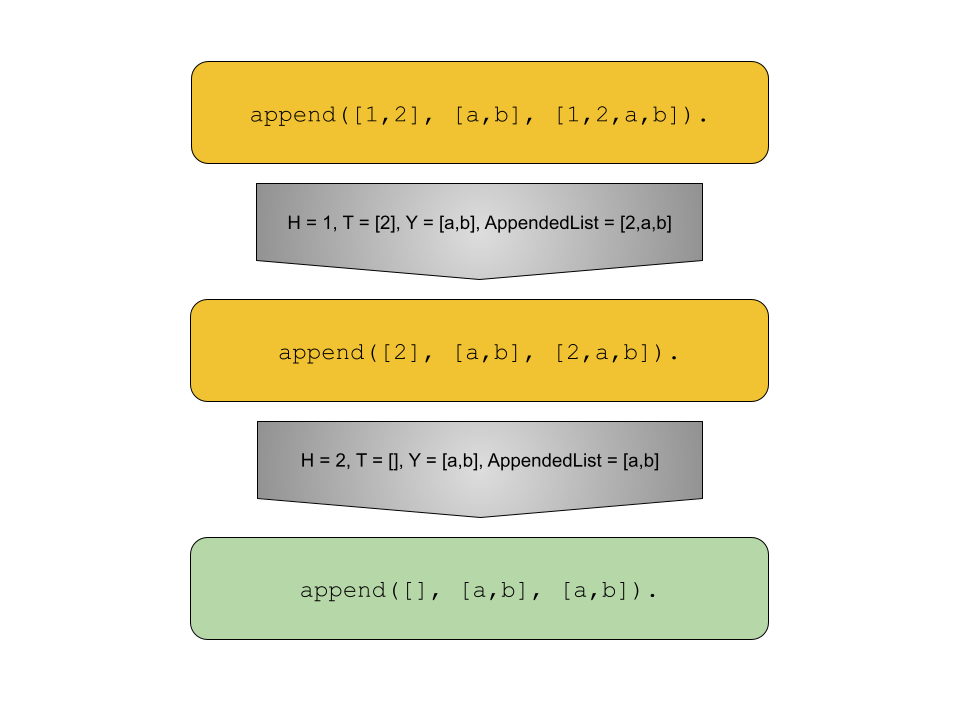

Let’s see how Prolog attempts to answer the query append([1,2], [a,b], [1,2,a,b]).

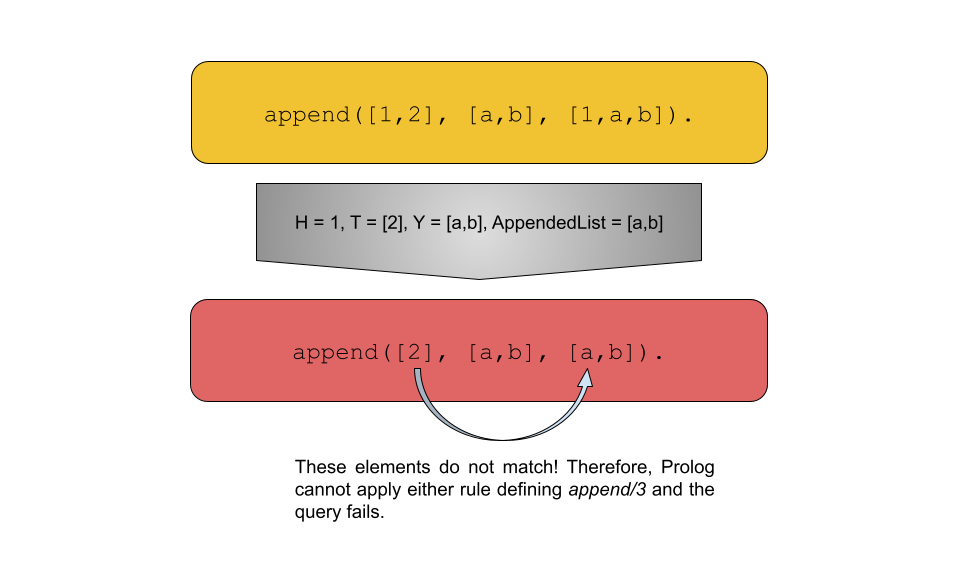

And now let’s look at it’s operation for the query append([1,2], [a,b], [1,a,b]).

It’s also natural to look at append/3 as a tool to “assign” a variable to be the result of appending two lists:

?- append([1,2,3], [a,b,c], Z).

Z = [1, 2, 3, a, b, c].

Here we are asking Prolog to assign variable Z to be a list that holds the appended contents of the lists in the first two arguments.

Look at Append From a Different Angle

We’ve seen append/3 in action so far in a procedural way – answering whether two lists are equal to one another and “assigning” a variable to a list that holds the contents of another two lists appended to one another. But earlier I said that append/3 has some magical powers.

If we look at append/3 from a different angle, the declarative angle, we can see how it can be used to generate all the different combinations of two lists that, when appended together, yield a third list! For example,

?- append(X, Y, [1,2,3]).

X = [],

Y = [1, 2, 3] ;

X = [1],

Y = [2, 3] ;

X = [1, 2],

Y = [3] ;

X = [1, 2, 3],

Y = [] ;

Wow. That’s pretty cool! Prolog is telling us that it can figure out three different combinations of lists that, when appended together, will equal the list [1,2,3]. I mean, if that doesn’t make your blood boil, I don’t know what will.

Let’s Ride the Thoroughbred

The power of append/3 makes it useful in so many different ways. When I started learning Prolog, the resource I was using (Learn Prolog Now (Links to an external site.)) spent an inordinate amount of time discussing append/3 and it’s utility. It took me a long time to really understand the author’s point. A long time.

Prefix and Suffix

Let’s take a quick look at how to define a rule prefix/2. prefix/2 takes two arguments – a possible prefix, PP, and a list, L – and determines whether PP is a prefix of L. We’ve gotten so used to writing recursive definitions, it seems obvious that we would define prefix/2 using that pattern. In the base case, an empty list is a prefix of any list:

prefix([], _).

(Remember that _ is “I don’t care.”). With that out of the way, we can say that PP is a prefix of L if

the head element of PP is the same as the head element of L, and the tail of PP is a prefix of the tail of L:

prefix([H|Xs], [H|Ys]) :- prefix(Xs, Ys).

Fantastic. That’s a pretty easy definition and it works in all the ways that we would expect:

?- prefix([1,2], [1,2,3]).

true.

?- prefix([1,2], [2,3]).

false.

?- prefix(X, [1,2,3]).

X = [] ;

X = [1] ;

X = [1, 2] ;

X = [1, 2, 3] ;

But, what if there was a way that we could write the definition of prefix/2 more succinctly! Remember, programmers are lazy – the fewer keystrokes the better!

Think about this alternate definition of prefix: PP is a prefix of L, when there is a (possibly empty) list, W (short for “whatever”), such that PP appended with W is equal to L. Did you see the magic word? Appended! We have append/3, so let’s use it:

prefix(PP, L) :- append(PP, _, L).

(Note that we have replaced W from a natural-language definition with _ because we don’t care about it’s value!)

We could go through the same process of defining suffix/2 recursively, or we could cut to the chase and define it in terms of append/3. Let’s save ourselves some time: SS is a suffix of L, when there is a (possibly empty) list, W (short for “whatever”), such that W appended with SS is equal to L. Let’s codify that:

suffix(SS, L) :- append(_, SS, L).

But, does it work?

?- suffix_append([3,4], [1,2,3,4]).

true.

?- suffix_append([3,5], [1,2,3,4]).

false.

?- suffix_append(X, [1,2,3,4]).

X = [1, 2, 3, 4] ;

X = [2, 3, 4] ;

X = [3, 4] ;

X = [4] ;

X = [] ;

Permutations

We’re all friends here, aren’t we? Good. I have no problem admitting that I am terrible at thinking about permutations of a set. I have tried and tried and tried to understand the section in Volume 4 of Knuth’s TAOCP (Links to an external site.) about generating permutations (Links to an external site.) but it’s just too hard for me. Instead, I just play around with them until I grok it. To help me play, I want Prolog’s help. I want Prolog to generate for me all the permutations of a given list. We will call this permute/2. Procedurally, permute/2 will say whether its second argument is a permutation of its first argument. Declaratively, permute/2 will generate a list of permutations of elements in the list in its first argument. Let’s work back from the end: We’ll see how it should work before actually defining it:

?- permutation([1,2,3], [3,1,2]).

true .

?- permutation([1,2,3], L).

L = [1, 2, 3] ;

L = [1, 3, 2] ;

L = [2, 1, 3] ;

L = [2, 3, 1] ;

L = [3, 1, 2] ;

L = [3, 2, 1] ;

false.

Cool. If I run permute/2 enough times I might start to understand them!

Now that we know the results of invoking permute/2, how are we going to define it? Again, let’s take the easy way out and see the definition and then walk through it piece-by-piece in order to understand its meaning:

permute([], []).

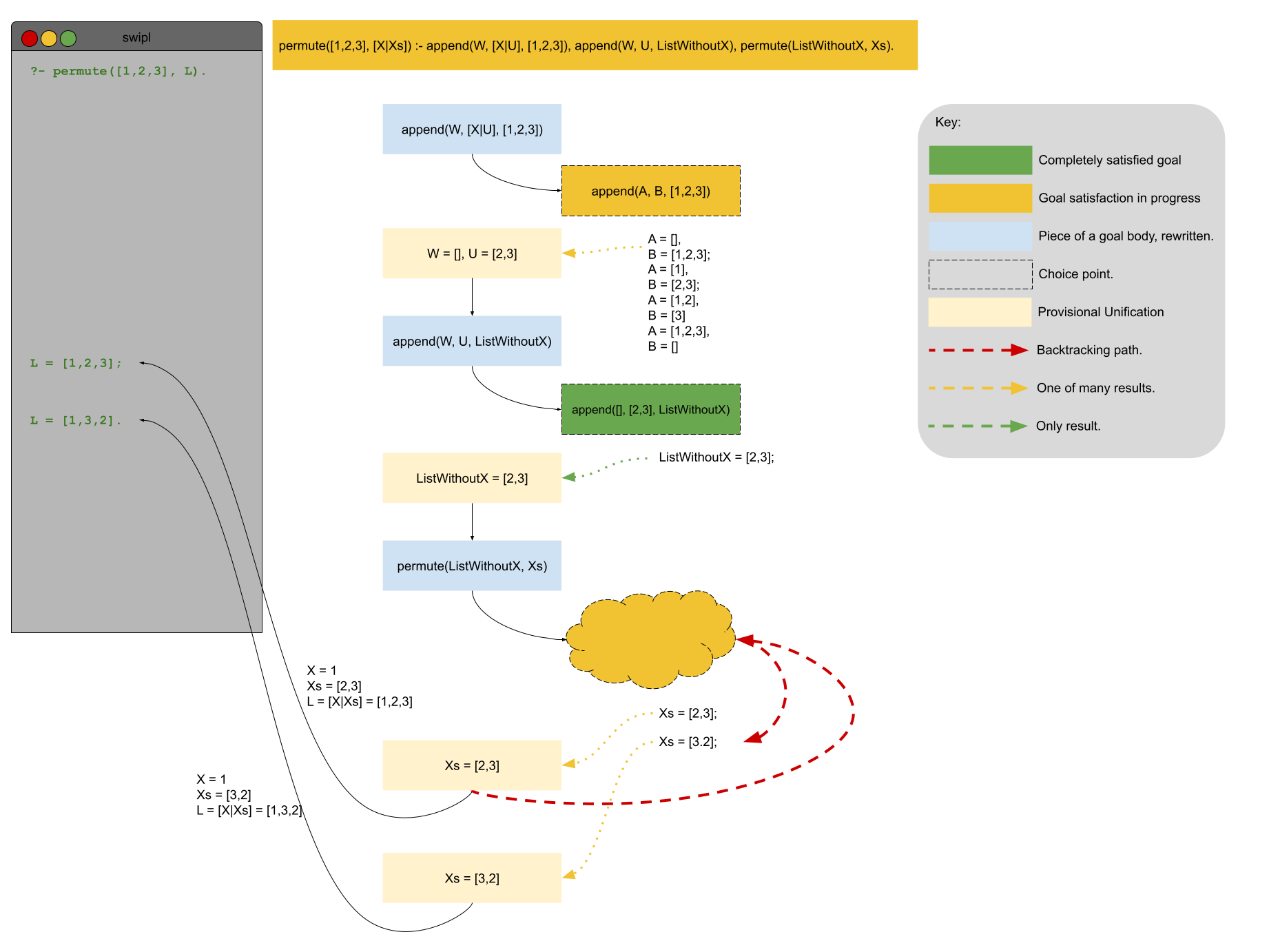

permute(List, [X|Xs]) :- append(W, [X|U], List), append(W, U, ListWithoutX), permute(ListWithoutX, Xs).

Well, the first rule is simple – the permutation of an empty list is just the empty list!

The second rule, well, not so much! There are three conditions that must be satisfied for a list defined as [X|Xs] to be a permutation of List.

Think of the first condition in a declarative sense: “Prolog, make me two lists that, when appended together, equal List. Name the first one W. And, while you’re at it, make sure that the first element in the second list is X and call the tail of the second list U. Thanks.”

Think of the second condition in a procedural sense: “Prolog, append W and U to create a new list named ListWithoutX.” The name ListWithoutX is pretty evocative because, well, it is a list that contains every element of List but X.

Finally, think of the third condition in a declarative sense: “I want Xs to be all the possible permutations of ListWithoutX – Prolog, make it so!”

Let’s try to put all this together into a succinct natural-language definition: A list whose first element is X and whose tail is Xs is a permutation of List if:

- X is one of the elements of List, and

- Xs is a permutation of the list List without element X.

Below is a visualization of the process Prolog takes to generate the first two permutations of [1,2,3]: