11/12/2021

If the append/3 predicate that we wrote on Wednesday is a horse that we can ride to accomplish many different tasks, then Prolog is like a wild stallion that tends to run in a direction of its choosing. We can use cuts to tame our mustang and make it go where we want it to go!

The Possibilities Are Endless

Let’s start the discussion by writing a merge/3 predicate. The first two arguments are sorted lists. The final argument should unify to the in-order version of the first two arguments merged. Before starting to write some Prolog, let’s think about how we could do this.

Let’s deal with the base cases first: When either of the first two lists are empty, the merged list is the non-empty list. We’ll write that like

merge(Xs, [], Xs).

merge([], Ys, Ys).

And now, for the recursive cases: We will call the first argument Left, the second argument Right, and the third argument Sorted. The first element of Left can be called HeadLeft and the rest of Left can be called TailLeft. The first element of Right can be called HeadRight and the rest of Right can be called TailRight. In order to merge, there are three cases to consider:

- HeadLeft is less than HeadRight

- HeadLeft is equal to HeadRight

- HeadRight is less than HeadLeft

For case (1), the head of the merged result is HeadLeft and the tail of the merged result is the result of merging TailLeft with Right. For case (2), the head of the merged result is HeadLeft and the tail of the merged result is the result of merging TailLeft with TailRight. For case (3), the head of the merged result is HeadRight and the tail of the merged result is the result of merging Left with TailRight.

It’s far easier to write this in Prolog than English:

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [X|Zs]) :- X<Y, merge(Xs, [Y|Ys], Zs).

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [X|Zs]) :- X=:=Y, merge(Xs, Ys, Zs).

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [Y|Zs]) :- Y<X, merge([X|Xs], Ys, Zs).

(Note: : is the “equal to” boolean operator in Prolog. See =:=/2 (Links to an external site.) for more information.

For merge/3, let’s write the base cases after our recursive cases. With that switcheroo, we have the following complete definition of merge/3:

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [X|Zs]) :- X<Y, merge(Xs, [Y|Ys], Zs).

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [X|Zs]) :- X=:=Y, merge(Xs, Ys, Zs).

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [Y|Zs]) :- Y<X, merge([X|Xs], Ys, Zs).

merge(Xs, [], Xs).

merge([], Ys, Ys).

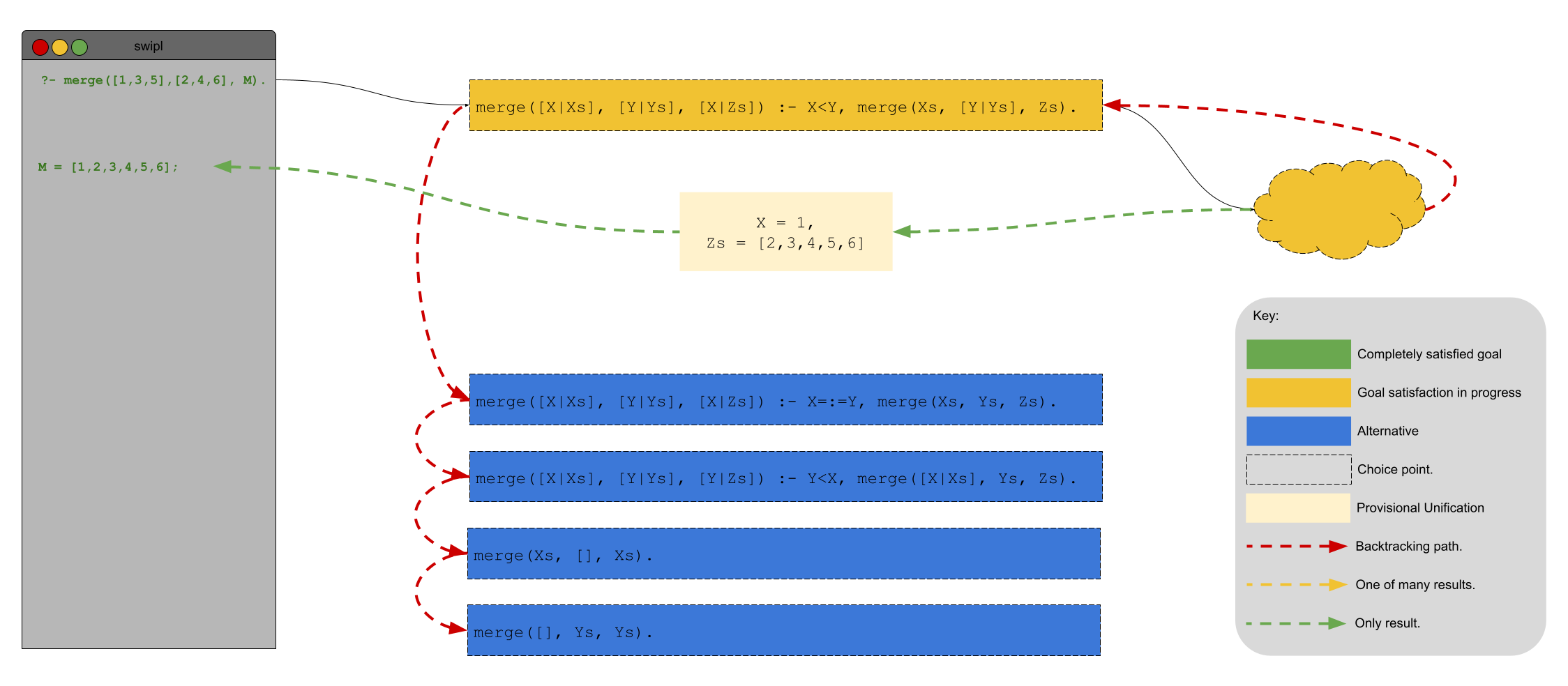

Let’s follow Prolog as it attempts to use our predicate to answer the query

merge([1, 3, 5], [2,4,6], M).

As we know, Prolog will search top to bottom when looking for ways to unify and the first rule that Prolog sees is applicable:

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [X|Zs]) :- X<Y, merge(Xs, [Y|Ys], Zs).

Why? Because Prolog sees X as 1 and Y as 2 and 1 < 2. Therefore, Prolog will complete its unification for this query by replacing it with another query:

merge([3,5], [2,4,6], Zs).

Once Prolog has completed that query, the response comes back:

M = [1,2,3,4,5,6]

Unfortunately, that’s not the whole story. While Prolog is off attempting to satisfy the subquery merge([3,5], [2,4,6], Zs)., it believes that there are still several other viable alternatives for satisfying our original query:

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [X|Zs]) :- X=:=Y, merge(Xs, Ys, Zs).

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [Y|Zs]) :- Y<X, merge([X|Xs], Ys, Zs).

merge(Xs, [], Xs).

merge([], Ys, Ys).

The result is that Prolog will have to use memory to remember those alternatives. As the lists that we ask Prolog to merge get longer and longer, that memory will have an impact on the system’s performance. However, we know that those other alternatives will never match and keeping them around is a waste. How do we know that? Well, if X < Y then it cannot be equal to Y and it certainly cannot be greater than Y. Moreover, the lists in the first two arguments cannot be empty. Overall, each of the possible rules for merge/3 are mutually exclusive. You can only choose one.

If there were a way to tell Prolog that those other possibilities are impossible after it encounters a matching rule that would save Prolog from having to keep them around. The good news is that there is!

We can use the cut (Links to an external site.) operator to tell Prolog that once it has “descended” down a particular path, there is no sense backtracking beyond that point to look for alternate solutions. The technical definition of a cut is

Discard all choice points created since entering the predicate in which the cut appears. In other words, commit to the clause in which the cut appears and discard choice points that have been created by goals to the left of the cut in the current clause.

Let’s rewrite our merge/3 predicate to take advantage of cuts and save some overhead:

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [X|Zs]) :- X<Y, !, merge(Xs, [Y|Ys], Zs).

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [X|Zs]) :- X=:=Y, !, merge(Xs, Ys, Zs).

merge([X|Xs], [Y|Ys], [Y|Zs]) :- Y<X, !, merge([X|Xs], Ys, Zs).

merge(Xs, [], Xs) :- !.

merge([], Ys, Ys) :- !.

Returning to the definition of cut, in the first rule we are telling Prolog (through our use of the cut) to disregard all choice points created to the left of the !. In particular, we are telling Prolog to forget about the choice it made that X < Y. The result is that Prolog is no longer under the impression that there are other rules that are applicable. Visually, the situation resembles

Dr. Cutyll and Mr. Unify

Cuts are not always so beneficial. In fact, their use in Prolog is somewhat controversial. A cut necessarily limits Prolog’s ability to backtrack. If the Prolog programmer uses a cut in a rule that is meant to be used declaratively (in order to generate values) and procedurally, then the cut may change the results.

There are two types of cuts. A green cut is a cut that does not change the meaning of a predicate. The cut that we added in the merge/3 predicate above is a green cut. A red cut is, technically speaking, a cut that is not a green cut. I know that’s a satisfying definition. Sorry. The implication, however, is that a red cut is a cut that changes the meaning of predicate.