11/17/2021

So far in this course we have covered lots of material. We’ve learned lots of definitions, explored lots of concepts and programmed in languages that we’ve never seen before. In all that time, though, we never really got to the bottom of one thing: What exactly is a language? In the final module of this course, we are going to cover exactly that!

Back to Basics

Let’s think way back to August 23 and recall two very important definitions: syntax and semantics. On that day we defined semantics as the effect of each statement’s execution on the program’s operation. We defined syntax as the rules for constructing structurally valid (note: valid, not correct) computer programs in a particular language. There’s that word again – language.

Before starting to define language, let me offer you two alternate definitions for syntax and semantics that draw out the distinction between the two:

- The syntax of a programming language specifies the form of its expressions, statements and program units.

- The semantics of a programming language specifies the meaning of its expressions, statements and program units.

It is interesting to see those two definitions side-by-side and realize that they are basically identical with the exception of a single word! One final note about the connection between syntax and semantics before moving forward: Remember how a well-designed programming language has a syntax that is evocative of meaning. In other words, a well-designed language might allow variables to contain a symbol like ? which would allow the programmer to indicate that it holds a Boolean.

Before we can specify a syntax for a programming language, we need to specify the language itself. In order to do that, we need to start by defining the language’s alphabet – finite set of characters that can be used to write sentences in that language. We usually denote the alphabet of a language with the \(\sum\). It is sometimes helpful to denote the set of all the possible sentences that can be written using the characters in the alphabet. We usually denote that with \(\sum\). For example, say that \(sum = \{a, b\}\), then \(\sum = \{a, b, aa, ab, ba, aaa, aab, aba, abb, …\}\). Notice that even though \(|\sum|\) is finite (that is, the number of elements in is finite), \(|\sum| = \infty\).

The alphabet of the C++ programming language is large, but it’s not infinite. However, the set of sentences that can be written using that alphabet is. But, as we all learn early in our programming career, just because you can write out a program using the valid symbols in the C++ alphabet does not mean the program is syntactically valid. The very job of the compiler is to distinguish between valid and invalid programs, right?

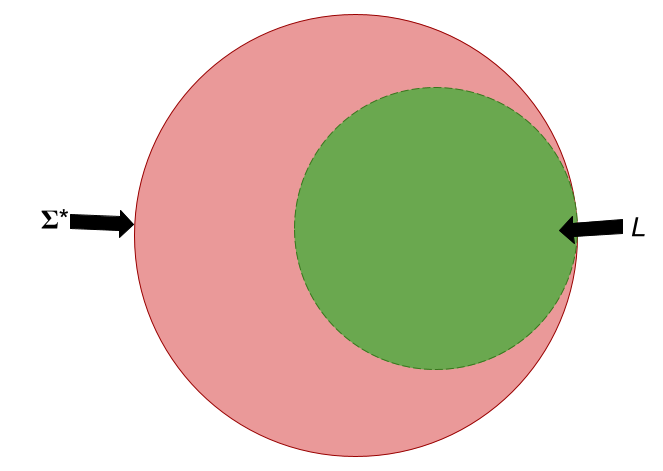

Let’s call the language that we are defining \(L\) and say that it’s alphabet is \(\sum\). \(L\) can be thought of as the set of all valid sentences in the language. Therefore, every sentence that is in \(L\) is in \(\sum\) – \(L \subseteq \sum\).

Look closely at the relationship between \(\sum\) and \(L\). While \(L\) never includes a sentence that is not included in \(\sum\), they can be identical! Think of some languages where any combination of characters from its alphabet are valid sentences! Can you come up with one?

The Really Bad Programmer

So, how can we determine whether a sentence made up of characters from the alphabet is in the language or not? We have to be able to answer this question – one of the fundamental jobs of the compiler, after all, is to do exactly that. Why not just write down every single valid sentence in a giant chart and compare the program with that list? If the program is in the list, then it’s a valid program! That’s easy.

Not so fast. Aren’t there an infinite number of valid C++ programs?

int main() {

if (true) {

if (true) {

if (true) {

...

std::cout << "Hello, World.";

}

}

}

}

Well, dang. There goes that idea.

I guess we need a concise way to specify how to describe sentences that are in the language and those that are not. Before we start to think about ways to do that, let’s think back to Prolog. One of the really neat things about Prolog was the ability to specify something that had, at the same time, an ability to recognize and generate valid solutions to a set of constraints. Even in our simplest Prolog example, we could write down a set of facts and the language could determine whether a student took a particular class (giving us a yes/no answer) or generate a list of the people who were taking a particular class!

It would be great to have a tool that does the same thing for languages – a common description that allows us to create something that recognizes and generates valid sentences in the language. We will do exactly that!

Language Classes

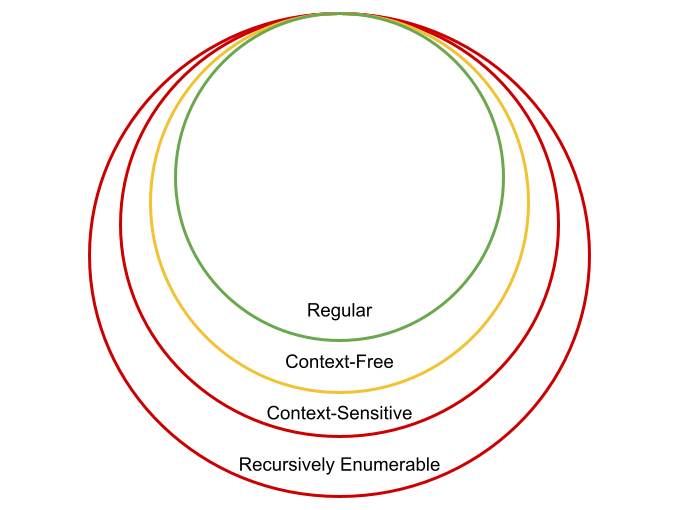

The famous linguist Noam Chomsky was the first to recognize how there is a hierarchy of languages. The hierarchy is founded upon the concept of how easy/hard it is to write a concise definition for the language’s valid sentences.

Each level of Chomsky’s Hierarchy, as it is called, contains the levels that come before it. Which languages belong to which level of the hierarchy is something that you will cover more in CS4040. (Note: The languages that belong to the Regular level can be specified by regular expressions (Links to an external site.). Something I know some of you have written before!)

For our purposes, we are going to be concerned with those languages that belong to the Context-Free level of the hierarchy.

Context-Free Grammars

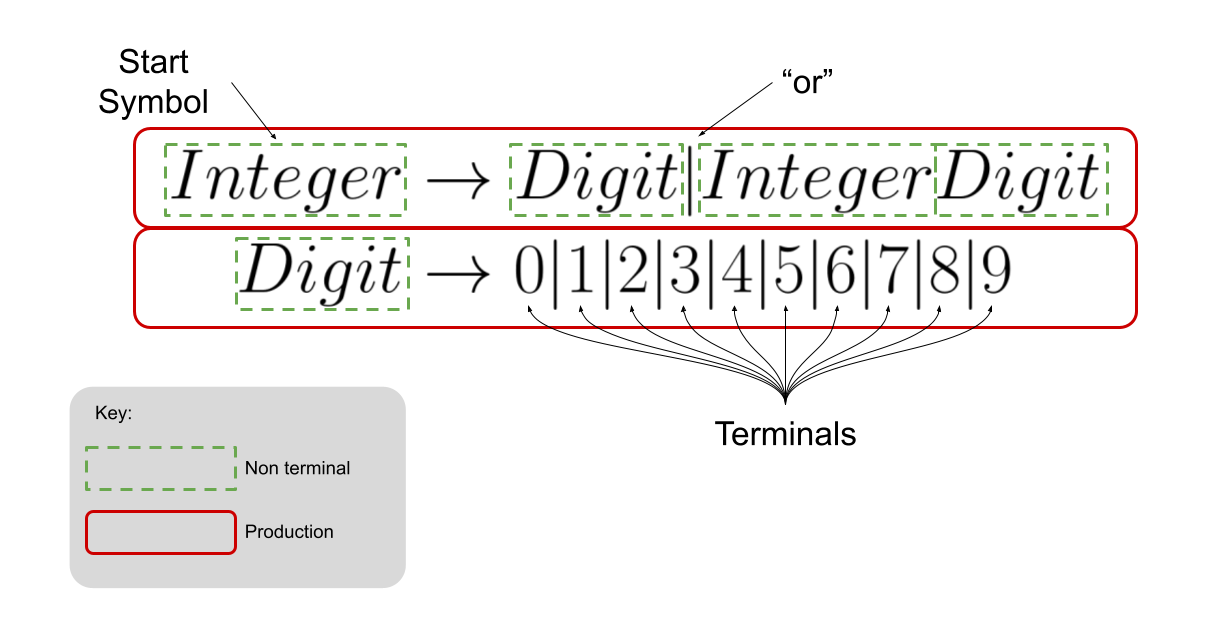

The tool that we can use to concisely specify a Context-Free language is called a Context-Free Grammar. Precisely, a Context-Free Grammar, , is a set of productions , a set of terminal symbols, , a set of non-terminal symbols, , one of which is named

and is known as the start symbol.

That’s a ton to take in. The fact of the matter, however, is that the vocabulary is intuitive once you see and use a grammar. So, let’s do that. We will define a grammar for listing/recognizing all the positive integers:

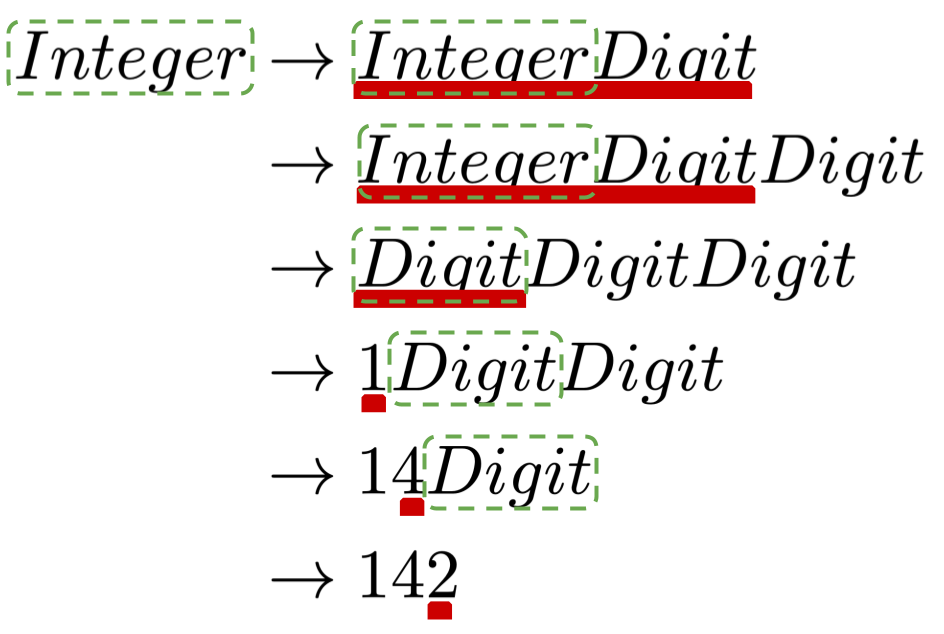

Now that we see an example of a grammar and its parts and pieces, let’s “read” it to help us understand what it means. Every valid integer in the language can be derived by writing down the start symbol and iteratively replacing every non-terminal according to a production until there are only terminals remaining! Again, that sounds complicated, but it’s really not. Let’s look at the derivation for the integer 142:

We start with the start symbol Integer and use the first production to replace it with one of the two options in the production. We choose to use the second part of the production and replace Integer with Integer Digit. Next, we use a production to replace Integer with Integer Digit again. At this point we have Integer Digit Digit. Next, we use one of the productions to replace Integer with Digit and we are left with Digit Digit Digit. Our next move is to replace the left-most Digit non-terminal with a terminal – the 1. We are left with 1 Digit Digit. Pressing forward, we replace the left-most Digit with 4 and we come to 14Digit. Almost there. Let’s replace Digit with 2 and we get 142. Because 142 contains only terminals, we have completed the derivation. Because we can derive 142 from the grammar, we can confidently say that 142 is in the language described by the grammar.