11/19/2021

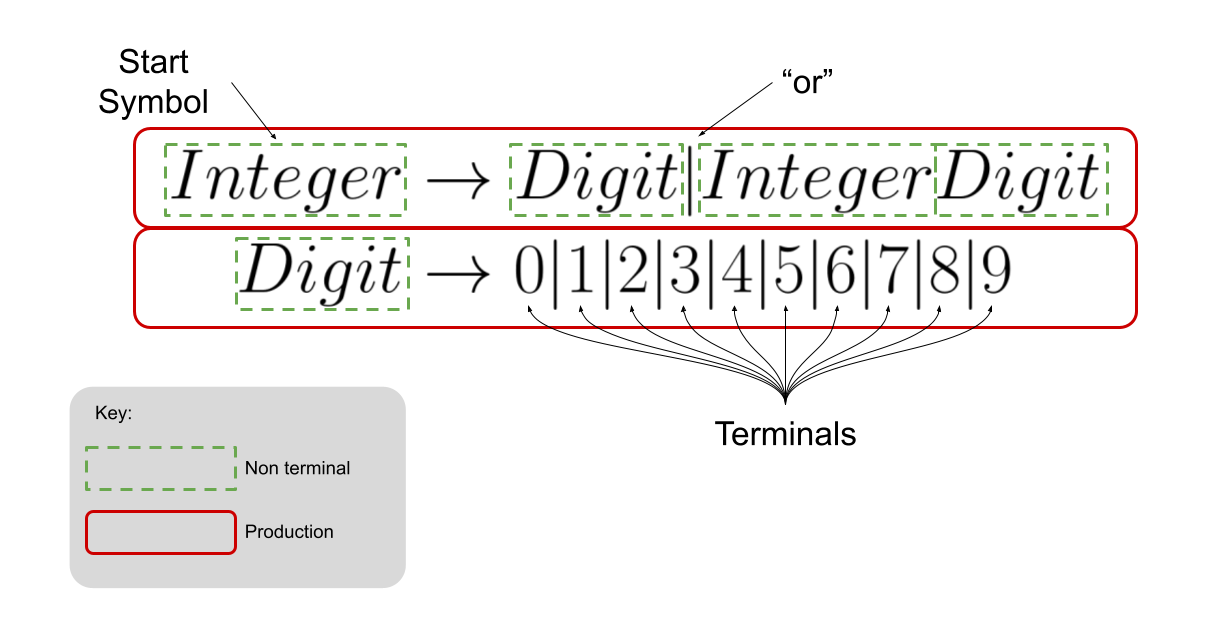

(Context-free) Grammars (CFG) are a mathematical description of a language-generation mechanism. Every grammar defines a language. The strings in that language are those that can be derived from the grammar’s start symbol. Put another way, a CFG describes a process by which all the sentences in a language can be enumerated, or generated.

Defining a way to generate all the sentences in a grammar is one way to specify a language. Another way to define a language is to build a tool that separates sentences that are in the language from sentences that are not in the language. This tool is known as a recognizer. There is a relationship between recognizers and generators and we will explore that in future lectures.

Grammatical Errors

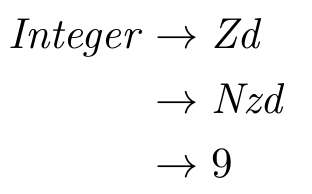

On Wednesday we worked with a grammar that purported to describe all the strings that looked like integers:

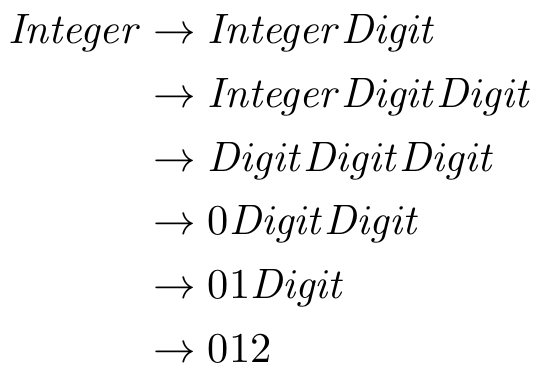

We performed a derivation using its productions to prove (by construction) that 142 is in the language. But, let’s consider this derivation:

We have just proven (again, by construction) that 012 is an integer. This seems funny. A number that starts with 0 (that is not just a 0) should not be deemed an integer. Let’s see how we can fix this problem.

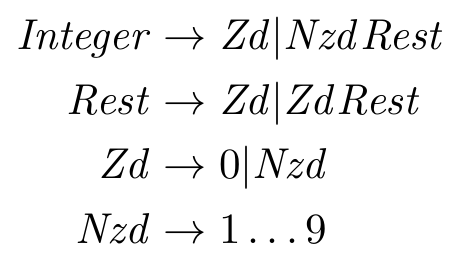

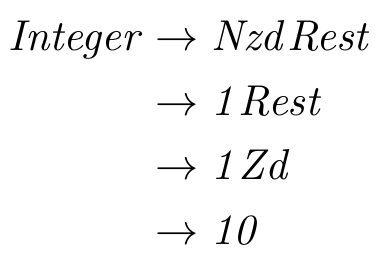

In order to guarantee that we cannot derive a number that starts with a 0 and deem it an integer, we will need to add a few more productions. First, let’s reconsider the production for the start symbol Integer. At the very highest level, we know that 0 is an integer. So, our start symbol’s production should handle that case.

With the base case accounted for, we next consider that an integer cannot start with a zero, but it can start with any other digit between 1 and 9. It seems handy to have a production for a non-terminal that expands to the terminals 1 through 9. We will call that non-terminal Nzd for non-zero digits. After the initial non-zero digit, an integer can contain zero or more digits between 0 and 9 (we can call this the rest of the integer). For brevity, we probably want a production that will expand to all the digits between 0 and 9. Let’s call that non-terminal Zd for zero digits. We’ll define it either as a 0 or anything in Nzd. If we put all of this together, we get the following grammar:

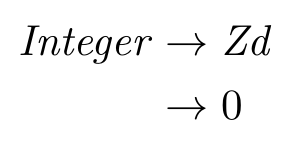

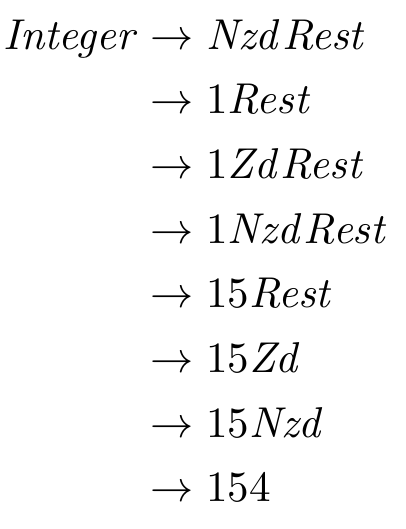

Let’s look at a few derivations to see if this gets the job done. Is 0 an integer?

And a single-digit integer?

How about an integer between 10 and 100, inclusive?

We are really cooking. Let’s try one more. Is a number greater than 100 derivable?

Think about this grammar and see if you can see any problems with it. Are there integers that cannot be derived? Are there sentences that can be derived that are not integers?

Trees or Derivations

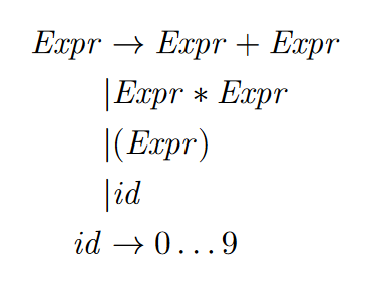

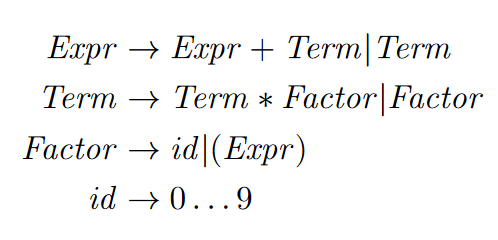

Let’s take a look at a grammar that will generate sentences that are simple mathematical expressions using the + and * operators and the numbers 0 through 9:

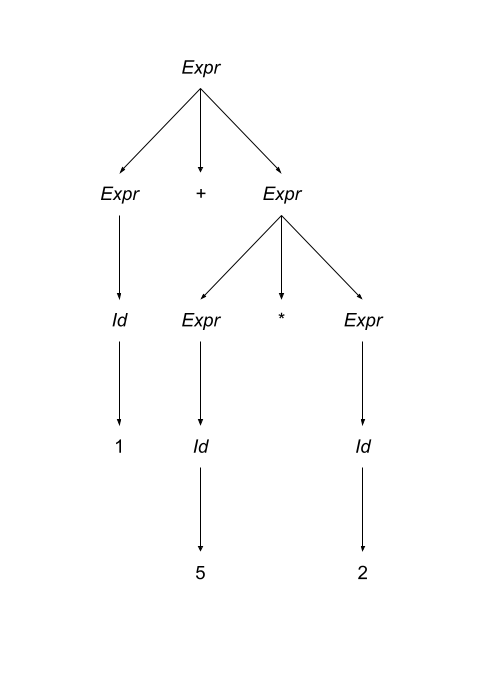

Until now we have used proof-by-construction through derivations to show that a particular string is in the language described by a particular grammar. What’s really cool is that any derivation can also be written in the form of a tree. The two representations contain the same information – a proof that a particular sentence is in a language. Let’s look at the derivation of the expression 1 + 5 * 2:

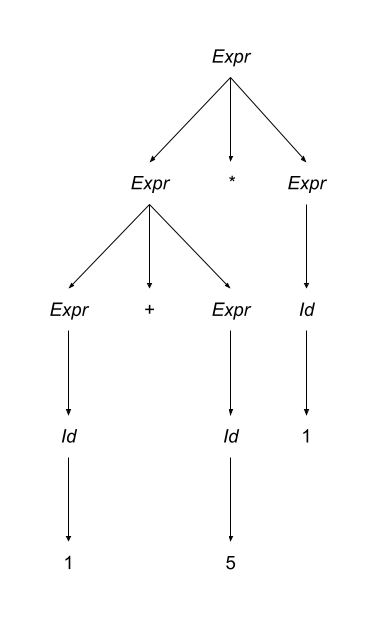

There’s only one problem with this derivation: Our choice of which production to apply to expand the start symbol was arbitrary. We could have just as easily used the second production and derived the expression 1 + 5 * 2:

This is clearly not a good thing. We do not want our choice of productions to be arbitrary. Why? When the choice of the production to expand is arbitrary, we cannot “encode” in the grammar any semantic meaning. (We will learn how to encode that semantic meaning below). A grammar that produces two or more valid parse trees for a particular sentence is known as an ambiguous grammar.

Let Me Be Clear

The good news is that we can rewrite the ambiguous grammar for mathematical expressions from above and get an unambiguous grammar. Like the way that we rewrote the grammar for integers, rewriting this grammar will involve adding additional productions:

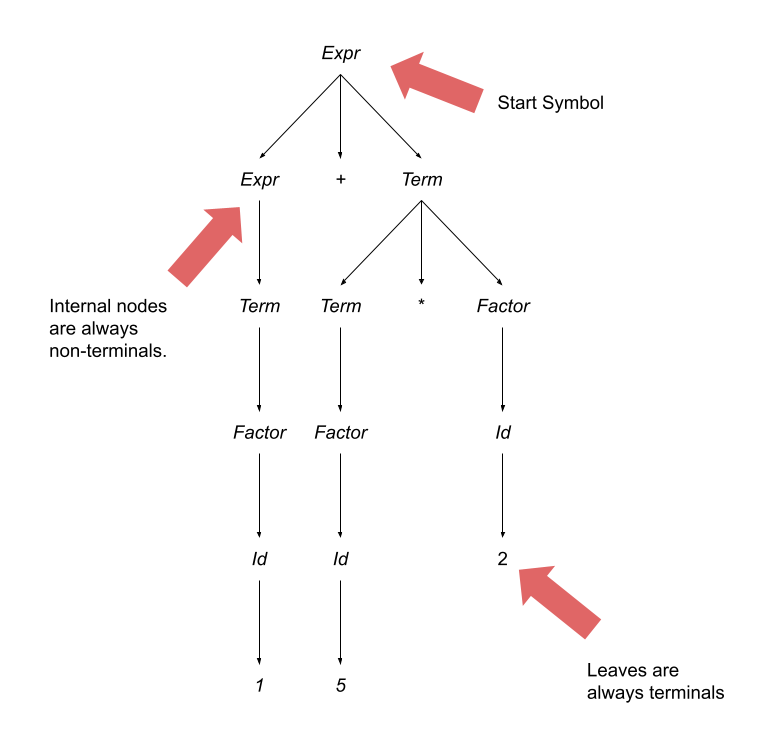

Using this grammar we have the following parse tree for the expression 1 + 5 * 2:

Before we think about how to encode semantic meaning in to a parse tree, let’s talk about the properties of a parse tree. The root node of the parse tree is always the start symbol of the grammar. The internal nodes of a parse tree are always non-terminals. The leaves of a parse tree are always terminals.

Making Meaning

If we adopt a convention that reading a parse tree occurs through a depth-first in-order traversal, we can add meaning to these beasts and their associated grammars. First, we can see how associativity is encoded: By writing all the productions so that “recursion” happens on the left side of any terminals (a so-called left-recursive production), we will arrive at a grammar that is left-associative. The converse is true – the productions whose recursion happens on the right side of any terminals (a right-recursive production) specifies right associativity. Second, we can see how precedence is encoded: The further away a production is from the start symbol, the higher the precedence. In other words, the precedence is inversely related to the distance from the start symbol. All alternate options for the same production have equal precedence.

Let’s look back at our grammar for Expr. A Term and an addition operation have the same precedence. A Factor and a multiplication operation have the same precedence. The production for an addition operation is left-recursive and, therefore, the grammar specifies that addition is left associative. The same is true for the multiplication operation.