11/29/2021

Recognizing vs Generating

We have talked at length about how, depending on your vantage point, you can look at predicates in Prolog as either declarative or procedural. Viewed from a declarative perspective, the predicates will generate all the values of a variable that will make the predicate true. Viewed from the other direction, predicates look more like traditional boolean-valued functions in a procedural (or OOP) programming language. The dichotomy between the declarative and procedural view has parallels in syntax and grammars. From one end of the PL football stadium, grammars are generators; from the other endzone they are recognizers.

We have seen the power of the derivation and the parse tree to generate strings that are in a language L defined by a grammar G. We can create a valid sentence in language L by repeated application of the productions in G to the sentential forms derived from G’s start symbol. Applying all the productions in all possible combinations will eventually enumerate all valid strings in the language L (don’t hold your breath for that process to finish!).

The only problem is that (with one modern exception ), our compilers don’t actually generate source code for us! It is the programmer – us! – who writes the source code and the compiler that checks whether it is a valid program. There are obviously myriad ways in which a programmer can write an invalid program in a particular programming language and the compiler can detect all of them. However, the easiest invalid programs for the compiler to detect are the ones that are not syntactically correct.

To reiterate, (most) programming languages specify their syntax using a (context-free) grammar (CFG) – the theoretical language L that we’ve talked about as being defined by a grammar G can actually be a programming language! Therefore, the source code for a program is technically just a particular sequence of terminals from L’s alphabet. For that sequence of terminals to be a valid program, it must be the final sentential form in some derivation following the productions of G.

In other words, the compiler is not a generator but rather a recognizer.

Parsers

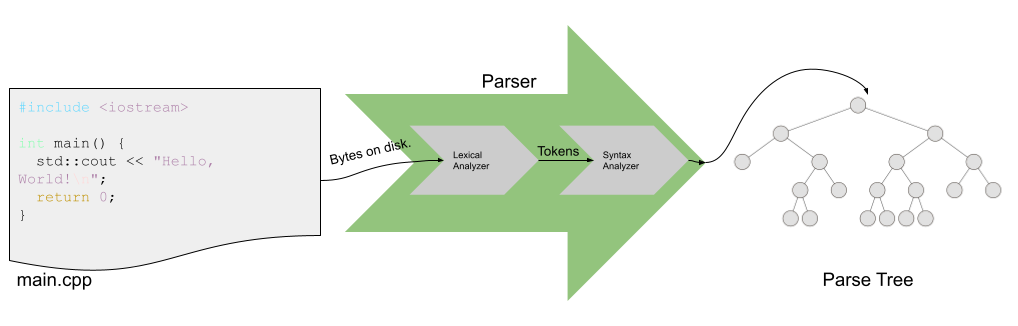

Recall from Chapter 2 of Sebesta (or earlier programming courses), the stages of compilation. The stage/tool that recognizes whether a particular sequence of terminals from a language’s alphabet is a valid program or not (the recognizer) is called parsing/a parser. Besides recognizing whether a program is valid, parsers convert the source code for a program written in a particular programming language defined according to a specific grammar into a parse tree.

What’s sneaky is that the parsing process is really two processes: lexical analysis and syntax analysis. Lexical analysis turns the bytes on the disk into a sequence of tokens (and associated lexemes). Syntax analysis turns the tokens into a parse tree.

We’ve seen several examples of languages defined by grammars and those grammars contain productions, terminals and nonterminals. We haven’t seen any tokens, though, have we? Well, tokens are an abstract way to represent groups of bytes in a file of source code in an abstract manner. The actual bytes that are in a group that are bundled together stay associated with the token and are known as lexemes. Tokenizing the input makes the syntax analysis process easier. Note: Read Sebesta’s discussion about the reason for separating lexical analysis from syntax analysis in Section 4.1 on (approximately pg. 143). Turtles All The Way Down

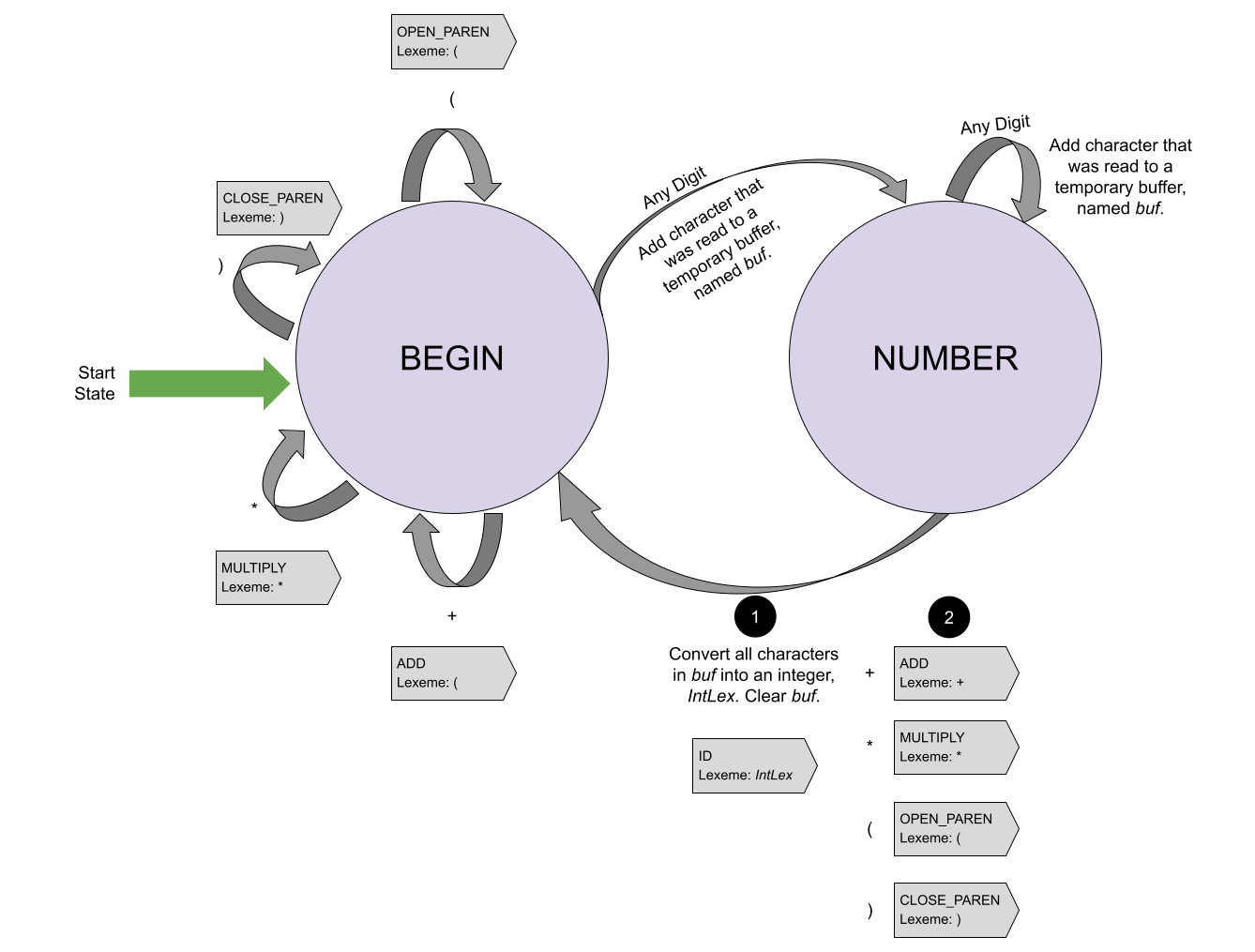

Remember the Chomsky Hierarchy of languages? Context-free languages can be described by CFGs. Slightly less complex languages are known as regular languages. Regular languages can be recognized by a logical apparatus known as a finite automata (FA). If you have ever written a regular expression then you have actually written a stylized FA. Cool, right?? You will learn more about FAs in CS4040, but for now it’s important to know the broad outlines of the definition of an FA because of the central role they play in lexical analysis. An FA is

- A (finite) set of states, S;

- A (finite) alphabet, A;

- A transition function, \(f : S, A \rightarrow S\), that takes two parameters (the current state [an element in S] and an element from the alphabet) and returns a new state;

- A start state (one of the states in S); and

- A set of accepting states (a subset of the states in S).

Why does this matter? Because we can describe how to group the bytes on disk into tokens (and lexemes) using regular languages. You probably have a good idea about what is going on, but let’s dig in to an example – that’ll help!

Lexical Analysis of Mathematical Expressions

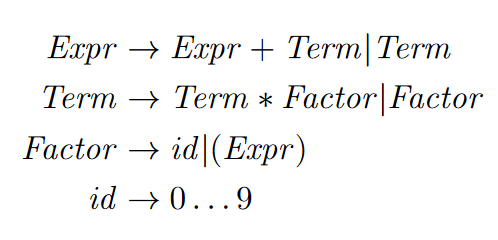

For the remainder of this edition, let’s go back to the (unambiguous) grammar of mathematical expressions:

Here’s a syntactically correct expression with labeled tokens and lexemes:

What do you notice? Well, the first thing that I notice is that in most cases, the lexeme value is actually, completely, utterly useless. For instance, what other logical grouping of bytes other than the one that represents the ) will be converted in to the CLOSE_PAREN token?

There is, however, one token whose lexeme is very important: the Id token. Why? Because that token can be any number! The actual lexeme of that Id makes a big difference when it comes time to actually evaluate the mathematical expression that we are parsing (if that is, indeed, the goal of the operation!).

Certitude and Finitude

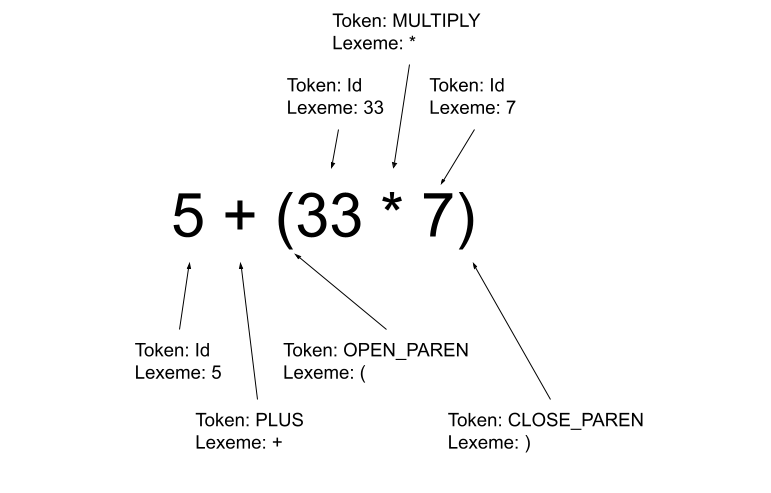

Let’s take a stab at defining the FA that we can use to convert a stream of bytes on disk in to a stream of tokens (and associated lexemes). Let yourself slip in to a world where you are nothing more than a robot with a simple memory: you can be in one of two states. Depending on the state that you are in, you are able to perform some specific actions depending on the next character that you see. The two states are BEGIN and NUMBER. When you are in the BEGIN state and you see a ), +, *, or ( then you simply emit the appropriate token and stay in the BEGIN state. If you are in the BEGIN state and you see a digit, you simply store that digit and then change your state to NUMBER. When you are in the NUMBER state, if you see a digit, you store that digit after all the digits you’ve previously seen and stay in the same state. However, when you are in the NUMBER state and you see a ), +, *, or (, you must perform three actions:

- Convert the string of digits that you are remembering into a number and emit a Id token with the converted value as the lexeme;

- Emit the token appropriate to the value you just saw; and

- Reset your state to BEGIN.

For as long as there are bytes in the input file, you continue to perform those operations robotically. The operations that I just described are the FA’s state transition function! See how each operation depends on the current state and an input? Those are the parameters to the state transition function! And see how we specified the state we will be in after considering the input? That’s the function’s output! Woah!

What’s amazing about all those words that I just wrote is that they can be turned into a picture that is far easier to understand:

Make the connection between the different aspects of the written and graphical description above and the formal components of an FA, especially the state transition function. In the image above, the state transition function is depicted with the gray arrows!

The Last Step…

There’s just one more step … we want to convert this high-level description of a tokenizer into actual code. And, we can! What’s more, we can use a technique we learned earlier this semester in order to do it! Consider that the tokenizer will work hand-in-hand with the syntax analyzer. As the syntax analyzer goes about its business of creating a parse tree, it will occasionally turn to the lexical analyzer and say, “Give me the next token!”. In between answers, it would be helpful if the tokenizer could maintain its state.

If that doesn’t sound like a coroutine, then I don’t know what does! Because a coroutine is dormant and not dead between invocations, we can easily program the tokenizer as a coroutine so that it remembers its state (either BEGIN or NUMBER) and other information (like the current digits that it is has seen [if it is in the NUMBER state] and the progress it has made reading the input file). Kismet!

To see such an implementation in Python, check here (Links to an external site.).