11/3/2021

It’s the 3rd day of November and we are about to switch to non-daylight savings time. What better way to celebrate the worst day of the year than switching our attention to a new topic!

I Do Declare

In this module we are going to focus on logic (also known as declarative) programming languages. Users of a declarative programming language declare the outcome they wish to achieve and let the compiler do the work of achieving it. This is in marked contrast to users of an imperative programming language who have to tell the compiler not only the outcome they wish to achieve but also how to achieve it. A declarative programming language does not have program control flow constructs, per se. Instead, a declarative programming language gives the programmer the power to control execution by means of recursion (again?? I know, sorry!) and backtracking. Backtracking is a concept that we will return to later. A declarative program is all about defining facts (either as axioms or as ways to build new facts from axioms) and asking questions about those facts. From the programming language’s perspective, those facts have no inherent meaning. We, the programmers, have to impugn meaning on to the facts. Finally, declarative programming languages do have variables, but they are nothing the variables that we know and love in imperative programming languages.

As we have worked through the different programming paradigms, we have discussed the theoretical underpinning of each. For imperative programming languages, the theoretical model is the Turing Machine. For the functional programming languages, the theoretical model is the Lambda Calculus. The declarative programming paradigm has a theoretical underpinning, too: first-order predicate calculus. We will talk more about that in class soon!

In the Beginning

Unlike imperative, object-oriented and functional programming languages, there is really only one extant declarative/logic programming language: Prolog.Prolog was developed by Alain Colmeraurer, Phillipe Roussel, and Robert Kowalski in order to do research in artificial intelligence and natural language processing

. Its official birthday is 1972.

Prolog programs are made up of exactly three components:

- Facts

- Rules

- Queries

The syntax of Prolog defines the rules for writing facts, rules and queries. Syntactic elements in Prolog belong to one of three categories:

- Atoms: The most fundamental unit of a Prolog program. They are simply symbols. Usually they are simply sequences of characters that begin with a lowercase letter. However, atoms can contain spaces (in which case they are enclosed in ’s) and they can start with uppercase letters (in which case they are wrapped with ’s).

- Variables: Like atoms, but variables always start with uppercase letters.

- Functors: Like atoms, but functors define relationships/facts.

If Prolog is a logic programming language, there must be some means for specifying logical operations. There is! In the context of specifying a rule, the and operation is written using a ,. In the context of specifying a rule, the or operation is written using a ;. Obviously!

The best way to learn Prolog is to start writing some programs. We’ll come back to the theory later!

Just The Facts

At its most basic, a Prolog program is a set of facts:

takes(jane, cs4999).

takes(alicia, cs2020).

takes(alice, cs4000).

takes(mary, cs1021).

takes(bob, cs1021).

takes(kristi, cs4000).

takes(sam, cs1021).

takes(will, cs2080).

takes(alicia, cs3050).

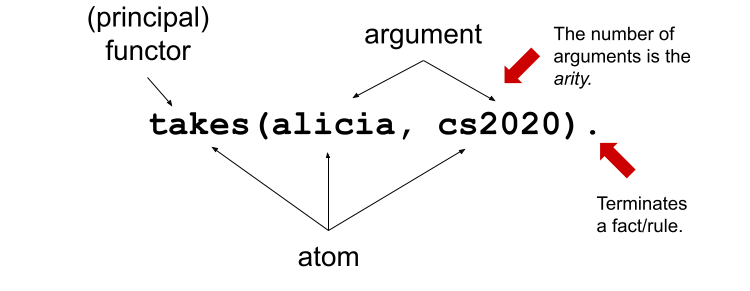

In relation to the first-order predicate logic that Prolog models, takes is a logical predicate. We’ll refer to them as facts or predicates, depending on what’s convenient. Formally, they predicates and facts are written as

Let’s read one of these facts in English:

takes(jane, cs4999).

could be read as “Jane takes CS4999.”. As programmers, we know what that means: the student named Jane is enrolled in the class CS4999. However, Prolog does not share our sense of meaning! Prolog simply thinks that we are defining one element of the takes relationship where jane is somehow related to cs4999. As a Prolog programmer, we could just has easily have written

tennis_shoes(jane, cs4999).

tennis_shoes(alicia, cs2020).

tennis_shoes(alice, cs4000).

tennis_shoes(mary, cs1021).

tennis_shoes(bob, cs1021).

tennis_shoes(kristi, cs4000).

tennis_shoes(sam, cs1021).

tennis_shoes(will, cs2080).

tennis_shoes(alicia, cs3050).

and gotten the same result! But, we programmers want to define something that is meaningful, so we choose to use atoms that reflect their semantic meaning. With nothing more than the facts that we have defined above, we can write queries. In order to interact with queries in real time, we can use the Prolog REPL. Once we have started the Prolog REPL, we will see a prompt like this:

?-

The world awaits …

To load a Prolog file in to the REPL, we will use the consult predicate:

?- consult('intro.pl').

true.

The Prolog facts, rules and queries in the intro.pl file are now available to us. Assume that intro.pl contains the takes facts from above. Let’s make some queries:

?- takes(bob, cs1021).

true.

?- takes(will, cs2080).

true.

?- takes(ali, cs4999).

false.

These are simple yes/no queries and Prolog obliges us with terse answers. But, even with the simple facts shown above, Prolog can be used to make some powerful inferences. Prolog can tell us the names of all the people it knows who are taking a particular class:

?- takes(Students, cs1021).

Students = mary ;

Students = bob ;

Students = sam.

Wow! Here Prolog is telling us that there are three different values of the Students variable that will make the query true: mary, bob and sam. In the lingo, Prolog is unifying Students with the values that will make our query true. Let’s go the other way around:

?- takes(alicia, Classes).

Classes = cs2020 ;

Classes = cs3050.

Here Prolog is telling us that there are two different classes that Alicia is taking. Nice.

That’s great, but pretty limited: it’s kind of terrible if we had to write out each fact explicitly! The good news is that we don’t have to do that! We can use a Prolog rule to define facts based on the existence of other facts. Let’s define a rule which will tell us the students who are CS majors. To be a CS major, you must be taking (exactly) two classes:

cs_major(X) :- takes(X, Y), takes(X, Z), Y @< Z.

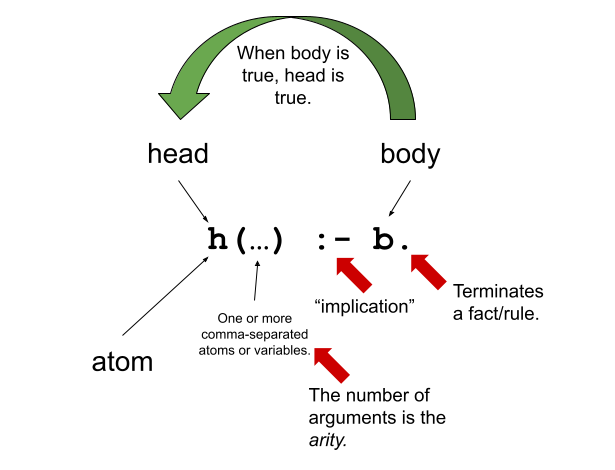

That’s lots to take in at first glance. Start by looking at the general format of a rule:

Okay, so now back to our particular rule that defines what it means to be a CS Major. (For the purposes of this discussion, assume that the @< operator is “not equal”). Building on what we know (e.g., , is and, :- is implication, etc), we can read the rule like: “X is a CS Major if X takes class Y and X takes class Z and class Y and Z are not the same class.” Pretty succinct definition.

To make the next few examples a little more meaningful, let’s update our list of facts before moving on:

takes(jane, cs4999).

takes(alicia, cs2020).

takes(alice, cs4000).

takes(mary, cs1021).

takes(bob, cs1021).

takes(bob, cs8000).

takes(kristi, cs4000).

takes(sam, cs1021).

takes(will, cs2080).

takes(alicia, cs3050).

With that, let’s find out if our rule works as intended!

?- cs_major(alicia).

true ;

false.

Wow! Pretty cool! Prolog used the rule that we wrote, combined it with the facts that it knows, and inferred that Alicia is a CS major! (For now, disregard the second False – we’ll come back to that!). Like we could use Prolog to generate the list of classes that a particular student is taking, can we ask Prolog to generate a list of all the CS majors that it knows?

?- cs_major(X).

X = alicia ;

X = bob ;

false.

Boom!