11/5/2021

*The retreat to move forward.

Backtracking

In today’s lecture, we discussed the concepts of backtracking and choice points in order to learn how Prolog can determine the meaning of our programs.

There is a formal definition of choice points and backtracking from the Prolog glossary:

backtracking: Search process used by Prolog. If a predicate offers multiple clauses to solve a goal, they are tried one-by-one until one succeeds. If a subsequent part of the proof is not satisfied with the resulting variable binding, it may ask for an alternative solution, causing Prolog to reject the previously chosen clause and try the next one.

There are lots of undefined words in that definition! Let’s dig a little deeper.

A predicate is like a boolean function. A predicate takes one or more arguments and yields true/false. As we said at the outset of our discussion about declarative programming languages, the reason that a predicate may yield true or false depends on the semantics imposed upon it from the outside. A predicate is a term borrowed from first-order logic, a topic that we will return to in later lectures.

Remember our takes example from previous lectures? takes is a predicate! takes has two arguments and returns a boolean.

In Prolog, rules and facts are written to define predicates. A rule defines the conditions under which a predicate is true using a body – a list of other predicates, logical conjunctives, implications, etc. See The Daily PL - 11/3/2021 for additional information about rules. A fact is a rule without a body and unconditionally defines that a certain relationship is true for a predicate.

related(will, bill).

related(ali, bill).

related(bill, william).

related(X, Y) :- related(X, Z), related(Z, Y).

In the example above, related is a predicate defined by facts and rules. The facts and rules above are the clauses of the predicate.

choicepoint: A choice point represents a choice in the search for a solution. Choice points are created if multiple clauses match a query or using disjunction (;/2). On backtracking, the execution state of the most recent choice point is restored and search continues with the next alternative (i.e., next clause or second branch of ;/2).

That’s a mouthful! I think that the best way to understand this is to look at backtracking in action and see where choice points exist.

Give and Take

Remember the takes predicate that we defined in the last class:

takes(jane, cs4999).

takes(alicia, cs2020).

takes(alice, cs4000).

takes(mary, cs1021).

takes(bob, cs1021).

takes(bob, cs8000).

takes(kristi, cs4000).

takes(sam, cs1021).

takes(will, cs2080).

takes(alicia, cs3050).

We subsequently defined a cs_major predicate:

cs_major(X) :- takes(X, Y), takes(X, Z), Y @< Z.

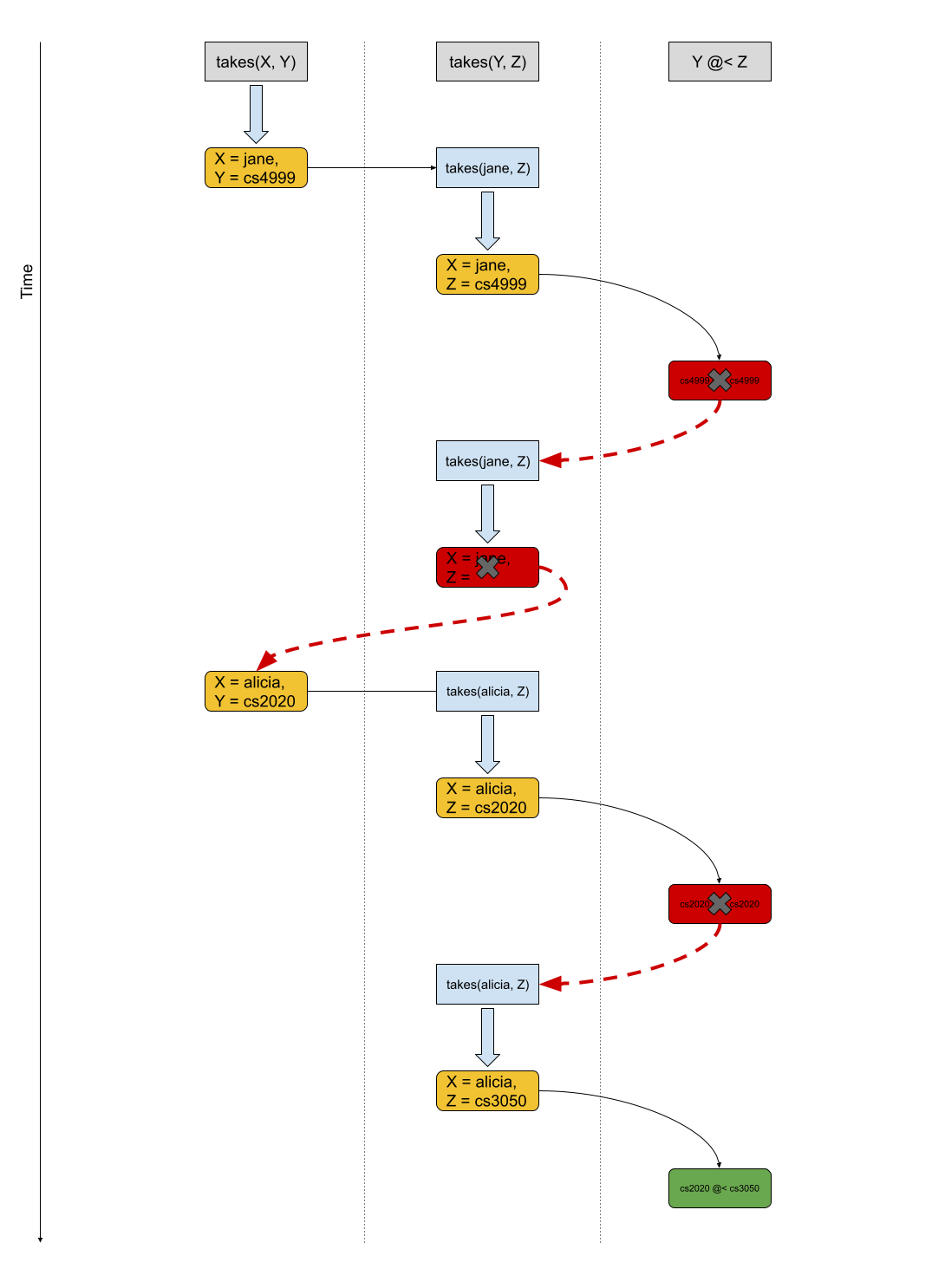

The cs_major predicate says that a student who takes two CS classes is a CS major. Let’s walk through how Prolog would respond to the following query:

cs_major(X).

To start, Prolog realizes that in order to satisfy our query, it has to at least satisfy the query

takes(X, Y).

So, Prolog starts there. In order to satisfy that query, it searches its knowledge base (its list of facts/rules that define predicates) from top to bottom. X and Y are variables and the first appropriate fact that it finds is

takes(jane, cs4999).

So, it unifies X with jane and Y with cs4999. Having satisfied that query, Prolog realizes that it must also satisfy the query:

takes(X, Z).

However, Prolog has already provisionally unified X with jane. So, Prolog really attempts to satisfy the query:

takes(jane, Z).

Great. For Prolog, attempting to satisfy this query is completely distinct from its attempt to satisfy the query takes(X, Y) which means that Prolog starts searching its knowledge base anew (again, from top to bottom!). The first appropriate fact that it finds that satisfies this query is

takes(jane, cs4999).

So, it unifies Z with cs4999. Having satisfied that query too, Prolog moves on to the third query:

Y @< Z.

Unfortunately, because X and Y are both unified to cs4999, Prolog fails to satisfy that query. In other words, Prolog realizes that its provisional unification of X with jane, Y with cs4999 and Z with cs4999 is not a way to satisfy our original query (cs_major(X)).

Does Prolog just give up? Absolutely not! It’s persistent. It backtracks! To where?

Well, according to the definition above, it backtracks to the most-recent choicepoint! In this case, the most recent choicepoint was its provisional unification of Z with cs4999. So, Prolog forgets about that attempt, and restarts the search of its knowledge base.

Where does it restart that search, though? This is important: It restarts its search where it left off. In other words, it starts at the first fact at takes(jane, cs4999). Because there are no other facts about classes that Jane takes, Prolog fails again, this time attempting to satisfy the query takes(jane, Z).

I ask again, does Prolog just give up? No, it backtracks again! This time it backtracks to its most-recent choicepoint. Now, that most recently choicepoint was its provisional unification of X with jane. Prolog forgets that attempt, and restarts the search of its knowledge base! Again, because this is the continuation of a previous search, Prolog begins where it left off in its top-to-bottom search of its knowledge base. The next fact that it see is

takes(alicia, cs2020)

So, Prolog provisionally unifies X with alicia and Y with cs2020. Having satisfied that query (for a second time!), Prolog realizes that it must also satisfy the query:

takes(X, Z).

However, Prolog has provisionally unified X with alicia. So, Prolog really attempts to satisfy the query:

takes(alicia, Z).

Great. For Prolog, attempting to satisfy this query is completely distinct from its attempt to satisfy the query takes(X, Y) and its previous attempt to satisfy the query takes(jane, Z). Therefore, Prolog starts searching its knowledge base anew (again, from top to bottom!). The first appropriate fact that it finds that satisfies this query is

takes(alicia, cs2020).

So, it unifies Z with cs2020. Having satisfied that query too, Prolog moves on to the third query:

Y @< Z.

Unfortunately, because Z and Y are both unified to cs2020, Prolog fails to satisfy that query. In other words, Prolog realizes that its provisional unification of X with alicia, Y with cs2020 and Z with cs2020 is not a way to satisfy our original query (cs_major(X)). Again, Prolog does not give up and it backtracks to its most recent choicepoint. The good news is that Prolog can satisfy the query

takes(alicia, Z)

a second way by unifying Z with cs3050. Prolog proceeds to the final part of the rule

X @< Y

which can be satisfied this time because cs3050 and cs2020 are different!

Victory!

Prolog was able to satisfy the original query when it unified X with alicia, Y with cs2020 and Z with cs3050.

Below is a visualization of the description given above:

A Prolog user at the REPL (or a Prolog program using this rule) could ask for all the ways that this query is satisfied. And, if the user/program does, then Prolog will backtrack as if it did not find a satisfactory unification for Z, Y or X (in that order!).* 11/5/2021