11/8/2021

In the true spirit of a picture being worth a thousand words , think of this Daily PL as a graphic novel.

Going Over Backtracking Again (see what I did there?)

In today’s lecture, we went deeper into the discussion of backtracking and saw its utility. In particular, we discussed the following Prolog program for generating all the integers.

generate_integer(0).

generate_integer(X) :- generate_integer(Y), X is Y + 1.

This is an incredibly succinct way to declare what it means to be an integer. This generator function is attributable to Programming in Prolog by Mellish and Clocksin (Links to an external site.). In other words, we know that it’s a reasonable definition.

As discussed in the description of Assignment 3, the best way to learn Prolog, I think, is to play with it! So, let’s see what this can do!

?- generate_integer(5).

true ;

In other words, it can be used to determine whether a given number is an integer. Awesome.

?- generate_integer(X).

X = 0 ;

X = 1 ;

X = 2 ;

X = 3 ;

X = 4 ;

X = 5 ;

X = 6

Woah, look at that … generate_integer/1 can do double duty and generate all the integers, too. Pretty cool!

The generation of the numbers using this definition is possible thanks to the power of backtracking. If you need a refresher on backtracking and/or choice points, I recommend previous Daily PLs.

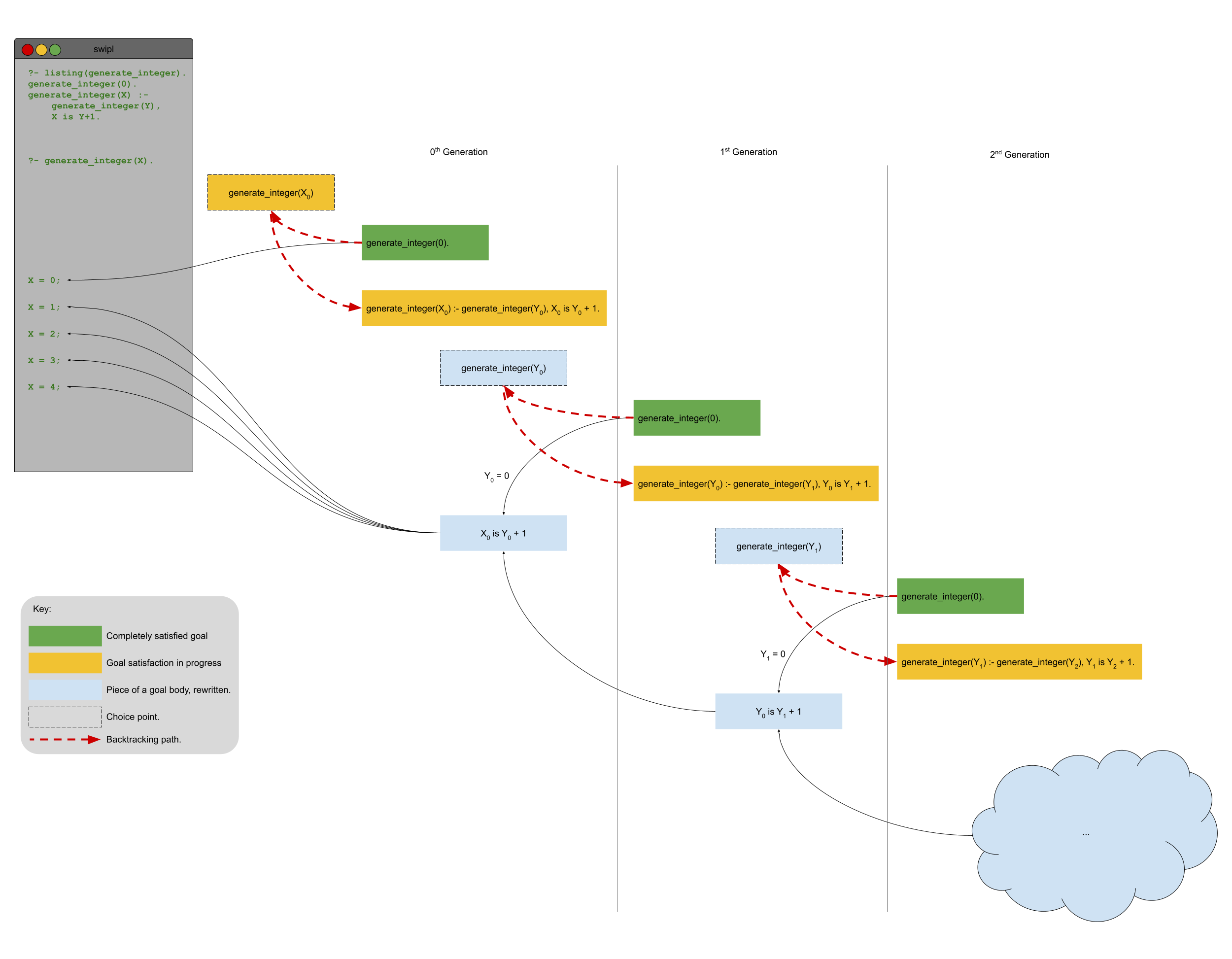

The (im)possibility of using words to describe the backtracking involved in generate_integer/1, led me to create the following diagram that attempts to illustrate the process. I encourage you to look at the diagram, run generate_integer/1 in swipl with trace enabled and ask any questions that you have! Again, this is not a simple concept, but once you understand what is going on, Prolog will begin to make more sense!

It may be necessary to use a high-resolution version of the diagram if you are curious about the details. Such a version is available in SVG format here.

Chasing Our Tails

Yes, I can hear you! I know, generate_integer/1 is not tail recursive. We learned that tail recursion is a useful optimization in functional programming languages (and even imperative programming languages). Does that mean that it’s an important optimization in Prolog?

To find out, I timed how long it took Prolog to answer the query

?- generate_integer(50000).

The answer? On my desktop computer, it took 1 minute and 48 seconds.

If we want something for comparison, we’ll have to come up with a tail-recursive version of generate_integer/1. Let’s call it generate_integer_tr/1 (creative, I know), and define it like:

generate_integer_tr(X) :- next_integer(0,X).

next_integer(J, J).

next_integer(J, L) :- K is J + 1, next_integer(K, L).

The fact next_integer(J, J) is a “trick” to define a base case for our definition in the same way that generate_integer(0) was a base case in the definition of generate_integer/1. To get a sense for the need for next_integer(J, J) think about what happens when the first query of next_integer(0,X) is performed in order to satisfy the query generate_integer_tr(50000). In this case, the next_integer(J, J) fact matches (convince yourself why! Hint: there are no restrictions on J). As a result, J unifies with the 0, and the X unifies with the J. That’s great, but (X = ) 0 does not equal 50000. So, Prolog does what?

In unison: BACKTRACKS.

The choice point is Prolog’s selection of next_integer(J, J), so Prolog tries again at the next possible fact/rule: next_integer(J, L) :- K is J + 1, next_integer(K, L). J is unified with 0, K is unified with 1 (J + 1) and Prolog must now satisfy a new goal: next_integer(1, L). Because this query for next_integer/1 is completely different than the one it is currently attempting to satisfy, Prolog starts the search anew at the top of the list of facts. The first fact to match? next_integer(J, J). Therefore, J unifies with 1, L unifies with J (making L 1), and X (from the initial query) unifies with L. Unfortunately, the result again does not satisfy our query. But, Prolog persists and backtracks but only as far as the second attempt to satisfy next_integer (using next_integer(J,J)). In much the same way that generate_integer/1 worked, Prolog continues to progress, then backtrack, then progress, then backtrack … while solving the generate_integer_tr(50000) query.

The difference between the two functions is that in next_integer/2, the recursive act is the last thing that is done. In other words, generate_integer_tr/1 is tail recursive.

Does this impact performance? Absolutely! On my desktop. Prolog can answer the query generate_integer_tr(50000). in 0.029 seconds. Yeow!