12/1/2021

Peanut Butter and Jelly

To reiterate, the goal of a parser is to convert the source code for a program written in a particular programming language defined according to a specific grammar into a parse tree. Parsing occurs in two parts: lexical analysis and syntax analysis. The lexical analyzer (what we studied in the previous lecture) converts the program’s source code (in the form of bytes on disk) into a sequence of tokens. The syntax analyzer, the subject of this lecture, turns the sequence of tokens in to a parse tree. The lexical analyzer and the syntax analyzer go hand-in-hand: As the syntax analyzer goes about its business of creating a parse tree, it will periodically turn to the lexical analyzer and say, “Give me the next token!”.

We saw algorithms for building a lexical analyzer directly from the language’s CFG. It would be great if we had something similar for the syntax analyzer. In today’s lecture we are going to explore just one of the many techniques for converting a CFG into code that will build an actual parse tree. There are many such techniques, some more general and versatile than others. Sebesta talks about several of these. If you take a course in compiler construction you will see those general techniques defined in detail. In this class we only have time to cover one particular technique for translating a CFG into code that constructs parse trees and it only works for a subset of all grammars.

With those caveats in mind, let’s dig in to the details!

Descent Into Madness

A recursive-descent parser is a type of parser that can be written directly from the structure of a CFG – as long as that CFG meets certain constraints. In a recursive descent parser built from a CFG G, there is a subprogram for every nonterminal in G. Most of these subprograms are recursive. A recursive-descent parser builds a parse tree from the top down, meaning that it begins with G’s start symbol and attempts to build a parse tree that represents a valid derivation whose final sentential form matches the program’s tokens. There are other parsers that work bottom up, meaning that they start by analyzing a sentential form made up entirely of the program’s tokens and attempt to build a parse tree that that “reduces” to the grammar’s start symbol. That the subprograms are recursive and that the parse tree is built top down, the recursive-descrent parser is aptly named.

We mentioned before that there are limitations on the types of languages that a recursive-descent parser can recognize. In particular, recursive-descent parsers can only recognize LL grammars. Those are grammars whose parse trees represent a leftmost derivation and can be built from a single left-to-right scan of the input tokens. To be precise, the first L represents the left-to-right scan of the input and the second L indicates that the parser generates a leftmost derivation. There is usually another restriction – how many lookahead tokens are available. A lookahead token is the next token that the lexical analyzer will return as it scans through the input. Limiting the number of lookahead tokens reduces the memory requirements of the syntax analyzer but restricts the types of languages that those syntax analyzers can recognize. The number of lookahead tokens is written after LL and in parenthesis. LL(1) indicates 1 token of lookahead. We will see the practical impact of this restriction later in this edition.

All of these words probably seem very arbitrary, but I think that an example will make things clear!

Old Faithful

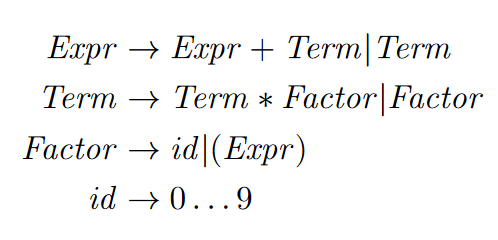

Let’s return to the grammar for mathematical expressions that we have been examining throughout this module:

We will assume that there are appropriately named tokens for each of the terminals (e.g, the ) token is CLOSE_PAREN) and that any numbers are tokenized as ID with the lexeme set appropriately.

According to the definition of a recursive-descent parser, we want to write a (possibly recursive) subprogram for each of the nonterminals in the grammar. The job of each of these subprograms is to parse the the upcoming tokens into a parse tree that matches the nonterminal. For example, the (possibly recursive) subprogram for Expr, Expr, parses the upcoming tokens into a parse tree for an expression and returns that parse tree. To facilitate recursive calls among these subprograms, each subprogram returns the root of the parse tree that it builds. The parser begins by invoking the subprogram for the grammar’s start symbol. The return value of that function call will be the root node of the parse tree for the entire input expression. Any recursive calls to other subprograms from within the subprogram for the start symbol will return parts of that overall parse tree.

I am sure that you see why each of the subprograms usually contains some recursive function calls – the nonterminals themselves are defined recursively.

How would we write such a (possibly recursive) subprogram to build a parse tree rooted at a Factor from a sequence of tokens?

There are two productions for a Factor so the first thing that the Factor subprogram does is determine whether it is parsing, for example, (5+2) – a parenthesized expression – or 918 – a simple ID. In order to differentiate, the function simply consults the lookahead token. If that token is an open parenthesis then it knows that it is going to be evaluating the production Factor \(\rightarrow ( Expr )\). On the other hand, if that token is an ID, then it knows that it is going to be evaluating the production Factor \(\rightarrow\) id. Finally, if the current token is neither an open parenthesis nor an ID, then that’s an error!

Let’s assume that the current token is an open parenthesis. Therefore, Factor knows that it should be parsing the production Factor \(\rightarrow ( Expr )\). Remember how we said that in a recursive-descent parser, each nonterminal is represented by a (possibly recursive) subprogram? Well, that means that we can assume there is a subprogram for parsing an Expr (though we haven’t yet defined it!). Let’s call that mythical subprogram Expr. As a result, the Factor subprogram can invoke Expr which will return a parse tree rooted at that expression. Pretty cool! Before continuing to parse, Factor will check Expr’s return value – if it is an error node, then parsing stops and Factor simply returns that error.

Otherwise, after successfully parsing an expression (by invoking Expr) the parser expects the next token to be a close parenthesis. So, Factor checks that fact. If everything looks good, then Factor simply returns the node generated by Expr – there’s no need to generate another node that just indicates an expression is wrapped in parenthesis. If the token after parsing the expression is not a close parenthesis, then Factor returns an error node.

Now, what happens if the lookahead token is an ID? That’s simple – Factor will just generate a node for that ID and return it!

Finally, if neither of those is true, Factor simply returns an error node.

Let’s make this a little more concrete by writing that in pseudocode. We will assume the following are defined:

- Node(T, X, Y, Z …): A polymorphic function that generates an appropriately typed node (according to T) in the parse tree that “wraps” the tokens X, Y, Z, etc. We will play fast and loose with this notation.

- Error(X): A function that generates an error node because token X was unexpected – an error node in the final parse tree will generate a diagnostic message.

- tokenizer(): A function that returns and consumes the next token from the lexical analyzer.

- lookahead(): A function that returns the lookahead token.

def Factor:

if lookhead() == OPEN_PAREN:

# Parsing a ( Expr )

#

# Eat the lookahead and move forward.

curTok = nextToken()

# Build a parse tree rooted at an expression,

# if possible.

nestedExpr = Expr()

# There was an error parsing that expression;

# we will return an error!

if type(nestedExpr) == Error:

return nestedExpr

# Expression parsing went well. We expect a )

# now.

if lookahead() == CLOSE_PAREN:

# Eat that close parenthesis.

nextToken()

# Return the root of the parse tree of the

# nested expression.

return nestedExpr

else:

# We expected a ) and did not get it.

return Error(lookahead())

else if lookahead() == ID:

# Parsing a ID

#

curTok = nextToken()

return Node(curTok)

else:

# Parsing error!

return Error(lookahead())

Writing a function to parse a Factor is relatively straightforward. To get a sense for what it would be like to parse an expression, let’s write a part of the Expr subprogram:

def Expr:

...

leftHandExpr = Expr()

if type(leftHandExpr) == Error:

return leftHandExpr

if lookahead() != PLUS:

curTok = nextToken()

return Error(curTok)

rightHandTerm = Term()

if type(rightHandTerm) == Error:

return rightHandTerm

return Node(Expr, leftHandExpr, rightHandTerm)

...

What stands out is an emerging pattern that each of the subprograms will follow. Each subprogram is slowly matching the items from the grammar with the actual tokens that it sees. The subprogram associated with each nonterminal parses the nonterminals used in the production, “eats” the terminals in those same productions and converts it all into nodes in a parse tree. The subprogram that calls subprograms recursively melds together their return values into a new node that will become part of the overall parse tree, one level up.

We Are Homefree

I don’t know about you, but I think that’s pretty cool – you can build a series of collaborating subprograms named after the nonterminals in a grammar that call each other and, bang!, through the power of recursion, a parse tree is built! I think we’re done here.

Or are we?

Look carefully at the definition of Expr given in the pseudocode above. What is the name of the first subprogram that is invoked? That’s right, Expr. When we invoke Expr again, what is the first subprogram that is invoked? That’s right, Expr again. There’s no base case – this spiral will continue until there is no more space available on the stack!

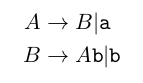

It seems like we may have run head-on into a fundamental limitation of recursive-descent parsing: The grammars that it parses cannot contain productions that are left recursive. A production A \(\rightarrow \ldots\) is (indirect) left recursive “when A derives itself as its leftmost symbol using one or more derivations.” In other words, \(A \rightarrow^{+} A \ldots \) is indirectly recursive where \(\rightarrow^{+} \)indicates one or more productions. For example, the production for A in grammar

is indirect left recursive because A → B → A \mathtt{b}.

A production A \(\rightarrow \ldots \)is direct left recursive when A derives itself as its leftmost symbol using one derivation (e.g., \(A \rightarrow A \ldots\). The production for Expr in our working example is direct left recursive.

What are we to do?

Note: The definitions of left recursion are taken from:

Allen B Tucker and Robert Noonan. 2006. Programming Languages (2nd. ed.). McGraw-Hill, Inc., USA.

Formalism To The Rescue

Stand back, we are about to deploy math!

There is an algorithm for converting productions that are direct-left recursive into productions that generate the same languages and are not direct-left recursive. In other words, there is hope for recursive-descent parsers yet! The procedure is slightly wordy, but after you see an example it will make perfect sense. Here’s the overall process:

For the rule that is direct-left recursive, A, rewrite all productions of A as \(A \rightarrow A\alpha_1 | A\alpha_2 | \ldots | A\alpha_n | \beta_1 | \ldots | \beta_n \) where all (non)terminals β_1 \ldots β_n are not direct-left recursive. Rewrite the production as

\(A \rightarrow \beta_{1}A’ | \beta_{2}A’ | \ldots | \beta_{n}A’ \\ A’ \rightarrow \alpha_{1}A’ | \alpha_{2}A’ | \ldots | \alpha_{n}A’ | \varepsilon\)

where \(\varepsilon\) is the erasure rule and matches an empty token.

I know, that’s hard to parse (pun intended). An example will definitely make things easier to grok:

In

\(Expr \rightarrow Expr + Term | Term\)

A is Expr, \(\alpha_1is + Term, \beta_1 is Term\). Therefore,

A \(\rightarrow \beta_{1}A’ \\ A’ \rightarrow \alpha_{1}A’ | \varepsilon \)

becomes

\(Expr \rightarrow Term Expr’ \\ Expr’ \rightarrow +TermExpr’ | \varepsilon\)

No sweat! It’s just moving pieces around on a chessboard!

The Final Countdown

We can make those same manipulations for each of the productions in the grammar in our working example and we arrive here:

\(\mathit{Expr} \rightarrow \mathit{Term}\mathit{Expr’} \\ \mathit{Expr’} \rightarrow + \mathit{Term}\mathit{Expr’} | \epsilon \\ \mathit{Term} \rightarrow \mathit{Factor}\mathit{Term’} \\ \mathit{Term’} \rightarrow * \mathit{Factor}\mathit{Term’} | \epsilon \\ \mathit{Factor} \rightarrow ( \mathit{Expr} ) | \mathit{id}\)

Now that we have a non direct-left recursive grammar we can easily write a recursive-descent parser for the entire grammar. The source code is available online and I encourage you to download and play with it!